A team of U.S. and Chinese scientists mapping oil pollution across the Earth’s oceans has found that more than 90% of chronic oil slicks come from human sources, a much higher proportion than previously estimated.

Their research, published in Science, is a major update from previous investigations into marine oil pollution, which estimated that about half came from human sources and half from natural sources.

“What’s compelling about these results is just how frequently we detected these floating oil slicks — from small releases, from ships, from pipelines, from natural sources such as seeps in the ocean floor and then also from areas where industry or populations are producing runoff that contains floating oil,” said Ian MacDonald, a professor in the Department of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Science at Florida State University and a paper co-author.

Oil slicks are microscopically thin layers of oil on the surface of the ocean. Massive oil spills can cause them, but they’re also widely and continuously produced by human activities and natural sources.

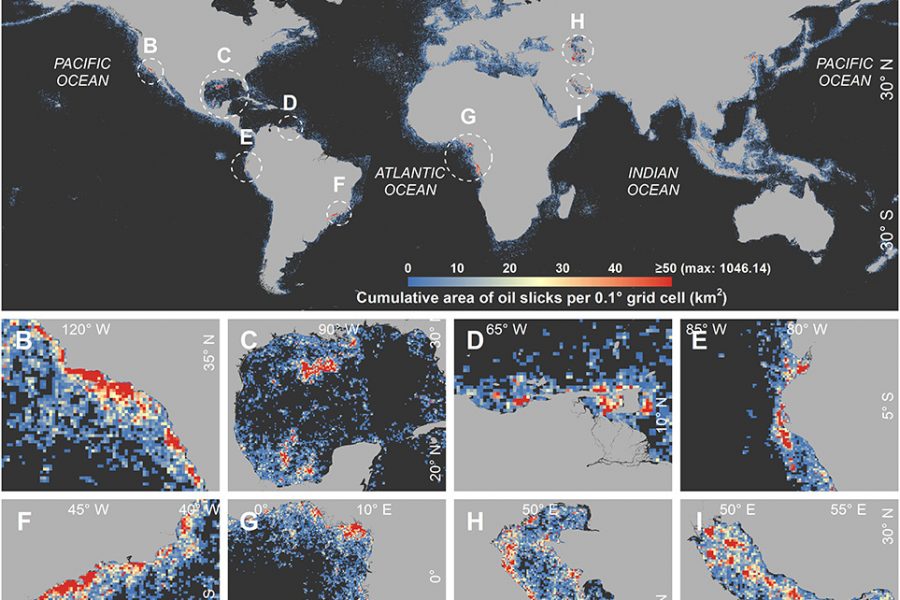

These short-lived patches of oil are continuously being moved around by wind and currents, while waves are breaking them apart, making investigations challenging. To find and analyze them, the research team used artificial intelligence to examine more than 560,000 satellite radar images collected between 2014 and 2019. That allowed them to determine the location, extent and probable sources of chronic oil pollution.

Even a miniscule amount of oil can have a big impact on plankton that make up the base of the ocean food system. Other marine animals, such as whales and sea turtles, are harmed when they contact oil as they come up to breathe.

“Satellite technology offers a way to better monitor ocean oil pollution, especially in waters where human surveillance is difficult,” said Yongxue Liu, a professor at Nanjing University’s School of Geographic and Oceanographic Science and the corresponding author. “A global picture can help focus regulation and enforcement to reduce oil pollution.”

Researchers found most oil slicks occurred near the coast. About half were within 25 miles of the coast, and 90% were within 100 miles. Offshore oil production accounted for less than two percent of the chronic oiling, but 21 distinct high-density belts of oil slicks were found to coincide with shipping routes.

“Satellite imagery offers an efficient way to monitor oil pollution in the ocean, especially in areas that are difficult for humans to get to,” said Chuanmin Hu, study co-author and professor at the University of South Florida’s College of Marine Science.

The researchers found relatively fewer oil slicks near oil platforms in the Gulf of Mexico compared to elsewhere on the globe, suggesting that regulation, enforcement and compliance from oil platform operators in U.S. waters reduces leakage.

“If we can take those lessons and apply them to places globally, where we have seen high concentrations of oil slicks, we could improve the situation,” MacDonald said.

Professor Yanzhu Dong of Nanjing University was the study’s lead author. Other co-authors included Yingcheng Lu of Nanjing University. This work was supported by the Key Research and Development Program of China.