A Florida State University research center is making a positive impact on literacy, at home and around the world.

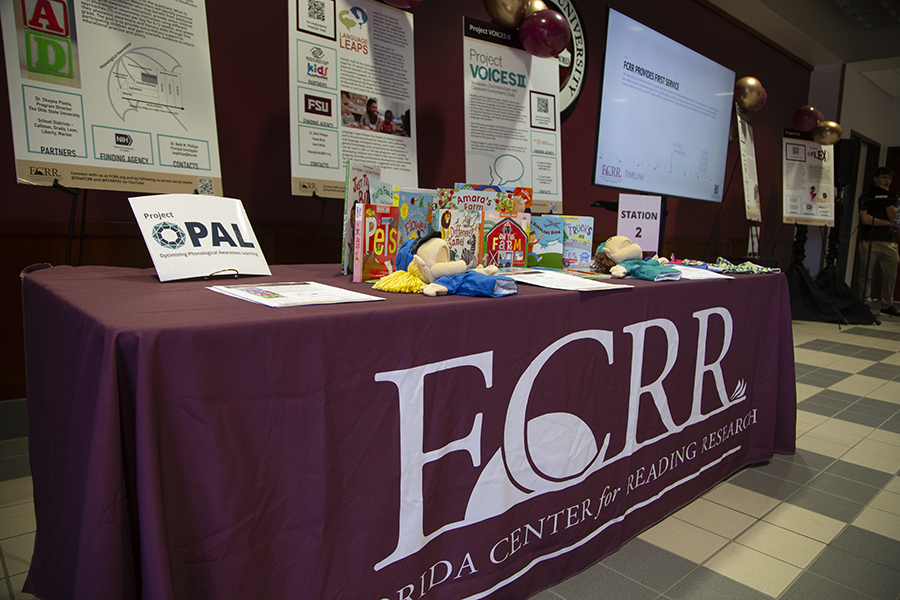

At an open house last month, the Florida Center for Reading Research (FCRR) opened its Innovation Park site to the public to showcase initiatives to help educators and the groundbreaking research led by the center’s dedicated faculty, students and staff.

“The research portfolio here is huge,” said FCRR Director Nicole Patton Terry. “It can be hard to grasp everything, but it’s much easier when you’re together and have the opportunity to talk about what we do.”

Representatives from the U.S. Department of Education (IES) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH), as well as senior faculty from other top universities, attended the event, highlighting the far-reaching impact and collaborative nature of FCRR’s work.

Attendees had the chance to tour FCRR’s facilities and see recent research projects, learn about how FCRR resources can help them with their work, and network with other educators and education researchers. An NIH meeting followed the open house.

“There’s so much research and innovation happening here that can be applied to a variety of settings, whether it be in classrooms, in specific interventions for individuals with disabilities, or in families, homes and communities,” Patton Terry said. “Our open house is an opportunity to focus on engagement. We make new discoveries here every day, but for all this discovery to truly make the impact we want to see in the world, we need to engage with our stakeholders in substantive ways through every step of the research process.”

GROUNDBREAKING RESEARCH

FCRR oversees a portfolio of more than $51 million of multi-year research projects around reading development, assessment, instruction and intervention, all aimed at contributing to scientific knowledge and benefiting students and educators. The open house was an opportunity to showcase some of that work.

Laura Steacy, an associate professor of Special Education and FCRR research faculty, researches early reading processes and development and how to support elementary school students who need help learning to read. She presented information about two ongoing studies: a project to explore instructional supports for children who are learning to read complex words, and a longitudinal study examining reading development in students from the start of kindergarten to the end of first grade.

Her work helps researchers and educators better understand predictors of later reading outcomes and use that knowledge to know when and how to successfully intervene to help struggling students.

“We know that early intervention is important for children who are at risk for reading disabilities, so understanding these underlying processes and predictors of later reading skill helps us to both identify children who might have reading disabilities or be at risk for reading disabilities like dyslexia and to intervene and get supports in for them as early as possible,” she said.

Nikita Potdar, manager of the Learning Brain Lab, presented research examining how sleep impacts mental health, academic achievement and overall well-being in students transitioning to high school. The research is especially relevant for Floridians because a new state law will change start times for high schools in August 2026.

Existing research suggests that even if high school students go to sleep later, thus getting the same amount of sleep as before a shift to school start times, a later start time is still beneficial because of teenagers’ adjusted biological rhythms.

“We’re especially interested in studying that right now to understand what that change entails and if that change is really benefiting students,” Potdar said.

Rachelle Johnson, doctoral student in Developmental Psychology and a Fellow with the FIREFLIES program, or Florida Interdisciplinary Research Fellows in Education Sciences, presented work on how the home literacy environment affects educational achievement of students with and without learning disabilities.

The researchers examined home literacy environments — attributes such as how many books were in a home, how often children looked at books and how often parents read to children.

They found that children with learning disabilities tended to have different home literacy environments than children without learning disabilities. They also found that the home literacy environment was equally important to reading achievement for students with and without learning disabilities.

“This work helps teachers and parents better understand the importance of building an environment that cultivates literacy and how they can support young learners,” Johnson said.

HELPING EDUCATORS MEET THEIR MISSION

The research happening at FCRR supports the work happening in classrooms around the nation and the world — and vice versa.

“These partnerships are not a one-way street,” Patton Terry said to educators gathered at the open house. “We learn because you tell us what it is that you need to improve outcomes for the people you work with and what we can do to support you in those efforts.”

The Florida Department of Education (DOE) has worked with FCRR since the center was established in 2002. Recently, FCRR partnered with the DOE to develop professional learning opportunities for teachers, literacy coaches and principals. The Journey to Literacy and Leadership program helps principals support the implementation of evidence-based and evidence-informed literacy practices in their schools. The Florida Reading Endorsement Pathways gives teachers the opportunity to earn a reading endorsement and implement evidence-based instructional strategies to impact student achievement.

Another initiative, the Florida Literacy Coach Endorsement Program, builds skills of literacy coaches, who help teachers improve student learning and literacy instruction.

“This ensures that we have people in the field who can support teachers on mastering their craft of teaching reading,” said Cari Miller, Vice Chancellor for Literacy Achievement at DOE. “Every child in the state of Florida is sitting in front of someone who can be successful in effectively teaching them how to read.”

That program helps the department to meet its literacy goals for students, which include ensuring that children enter kindergarten ready for school, that third graders graduate with the reading skills to be successful for the rest of their education, and that students graduate from high school.

“Being able to enter kindergarten ready for school and reading by the end of third grade is a massive predictor whether a child’s going to graduate high school,” Miller said. “Everything we do is built around those milestones.”