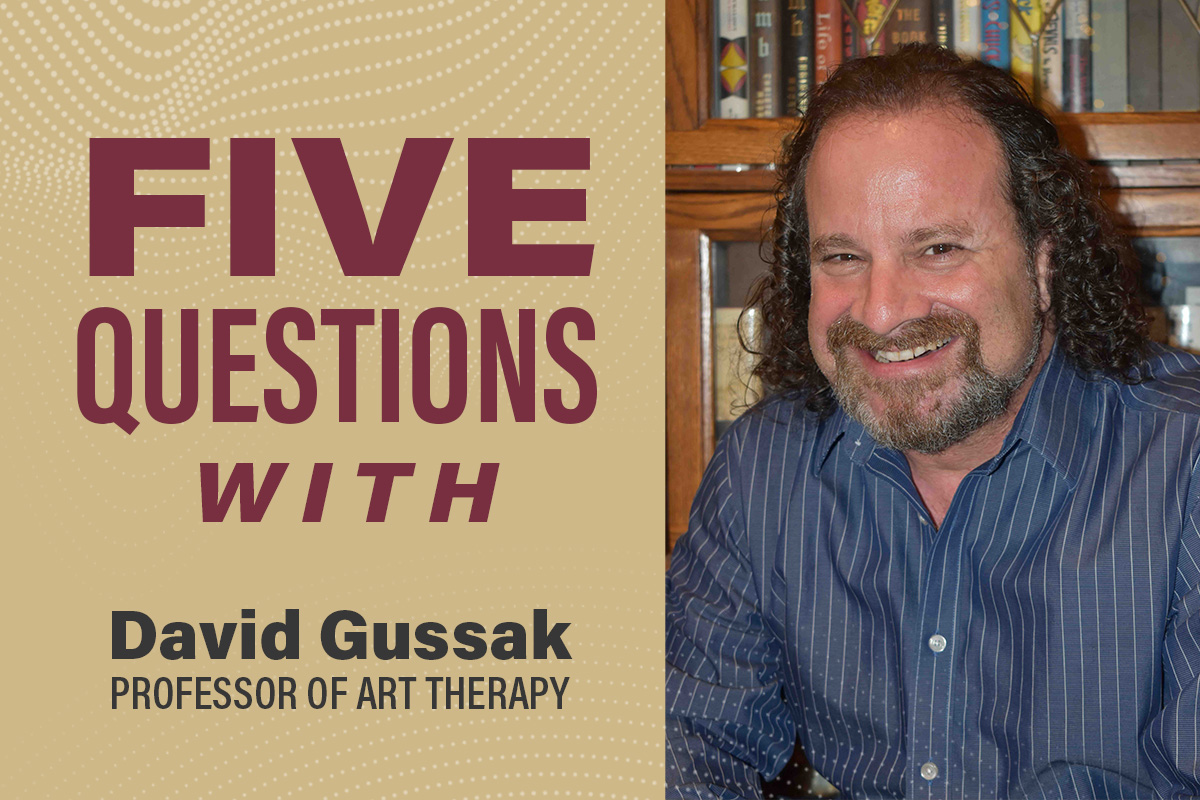

Dave Gussak, a professor in the Florida State University Graduate Art Therapy Program, has spent the past 30 years helping therapists, graduate students and clients understand the link between art and the human experience.

Recognized as a leading expert in art therapy in the correctional and forensic arenas, Gussak regularly presents on the subject in correctional settings. Among his many roles within FSU’s Department of Art Education, Gussak is the project coordinator for the FSU/FL Department of Corrections Art Therapy in Prisons Program. The program — comprised of four full-time art therapists working in nine prisons throughout the state — aims to give young adult inmates with special needs and obstacles the opportunity to earn their General Education Degrees while addressing mental health and emotional and behavioral issues through art therapy.

Gussak is the author of “Art on Trial: Art Therapy in Capital Murder Cases” and “Art and Art Therapy with the Imprisoned: Re-Creating Identity,” among other book chapters and blogs. His newest publication, “The Frenzied Dance of Art and Violence,” examines well-known artists, multiple murderers and violent offenders and the motivations behind their creations. It also looks at how their creative endeavors may reflect, contain, resist or sublimate their violent tendencies or volatile experiences, posing and reflecting on very important questions about humanity.

In the five questions below, Gussak explores his research and the importance of staying true to oneself through the heaviest of research materials.

What made you interested in this field of study?

This is a very complicated question. But if I have to put it simply, I have to begin with recognizing that I was a horrible high school student with little direction — the only high school course I did well in was art. This was well before I considered becoming an art therapist; frankly, I had no idea there was such a profession. My art teacher, Jay Palefsky, suggested that because I was good at art and liked people, I could perhaps combine the two, maybe become an “art therapist.” He also didn’t know there was such a thing and thought he had made up the concept. However, it wasn’t until I attended an art therapy workshop during my first year in college that I became entranced with the idea.

After graduating from Vermont College of Norwich University in 1991 with a master’s degree in art therapy, I got my first job as a rehabilitation/art therapist in a prison in Northern California. In 1997, after teaching workshops, lecturing for various educational programs, actively serving the art therapy community and publishing my first book, “Drawing Time: Art Therapy in Prisons and other Correctional Settings,” I decided I wanted to go into higher education. I secured my first teaching position at Emporia State University in 1998.

How I ended up becoming an art therapist, working with the prison population and serving the field were all through fortuitous happenstance, ultimately creating the path towards my life’s work. Everything happened at a crossroads, allowing me to make decisions to pursue what I love doing.

What realizations have you had about your field as you continue to research?

This latest, and final, book builds upon my experiences working as an art therapist in prisons and forensic systems for 30 years. Yet, I came to realize that I needed to expand upon what I have always believed, which was that while creative expression emerges from the same libidinal impulses as that of aggression, art-making can help turn aside violence.

As I started to dig deeper and really focus on exploring this natural interrelationship, I discovered that many well-known artists had complex relationships with violence and aggression. I began to recognize that certain motivations drove people to create art, and this art became a way to sublimate those motivations, however not always successfully. And then, of course, I started to recognize that there were some artists who emerged out of violent situations and used their creative expressions to escape, control, understand and rise above their violent environs.

One of the more important realizations, particularly when examining the creative products of very violent offenders, particularly serial killers and multiple murderers, was that art may not always succeed in re-directing, mitigating or containing these aggressive impulses. In some cases, art not only failed to mitigate or contain violence; it was used to feed violence and aggression. For example, it seemed that all the serial killers I examined in this book used their art as a weapon to perpetuate their narcissistic cycles and feelings of superiority and to perpetuate their harm against others.

How have your perspectives shifted since you began working in this field?

As I’ve been doing this for over 30 years, my approach and perspectives have continued to shift, evolve, develop and change. While I began with a psychodynamic perspective, I came to rely on and adopt the more sociological perspectives of Social/Symbolic Interactionism and Labeling Theory, a theoretical framework that sees society as the product of shared symbols, such as language. The more I do this, the more I realize I don’t have the answers and have come to learn so much from my students, from those I mentor around the world and from colleagues from very different fields and endeavors.

During all of this, my perspectives on the value of art-making and art therapy have become even more solidified, as I have seen time and time again the value of art-making with even the most egregious — considered by society as the most incorrigible — people.

What makes the “The Frenzied Dance of Art and Violence” unique?

With support from a Florida State University Council on Research and Creativity (CRC) grant and the Oxford University Press, I was able to rely on the works and psychobiographies of some of the most well-known artists and notoriously violent people to examine this complex, messy co-evolving, interrelationship, from which the book emerges.

The book took more than 8 years from ideation to completion and was finalized during a time of violence and resistance throughout our nation.

While my main goal of this book was to focus on violence and aggression and that, in some ways, to get people interested in this I would have to relay violent narratives, there are also elements of love, of overcoming obstacles, of striving for peace, that are intertwined throughout the chapters.

I trust people will come to realize that by exploring this complex interrelationship between art and violence, the book can’t help but provide an intricate, complicated and thought-provoking — sometimes controversial — examination, that may result in more questions than answers.

I have always placed value in recognizing that artists have an innate, healthy, aggressive drive they use to create art. I have always believed that art is valuable in that it allows us to deflect that aggression and transform it.

Yet, for me, in the process of researching for, reflecting on and writing this book, two seemingly antithetical and counterintuitive notions emerged:

- Aggression and violence are not always bad.

- Art is not always good.

Art is not innocuous, and it would be dangerous for us to think it is. In 320 pages, I explored the complexities that led to this conclusion.

What did you learn about yourself while writing this book?

I must be honest; my newest book took a lot out of me. I found myself getting lost in the topic and oftentimes, when deep in the research, focused on some of the more sordid details and inhuman actions, which led to nightmares and anxiety.

Early on, I felt trepidation that I was surrounded by violence, and couldn’t see a way out; world events certainly weren’t making it any easier for me to escape from that. However, as the writing process went on, I was able to find my voice, redirect and channel some of these apprehensions and discover the hope that indeed there are ways to address these misgivings and work with and through them.

Through it all, the main thing I had to do was hold on to my sense of humor. Humanity and humor begin with the same prefix, and without one, there is not the other. It requires gaining some distance and looking at it from a different — slightly askew — perspective. Thus, there remains a touch of humanity even when it seems absent — and I found humanity in doing this work.