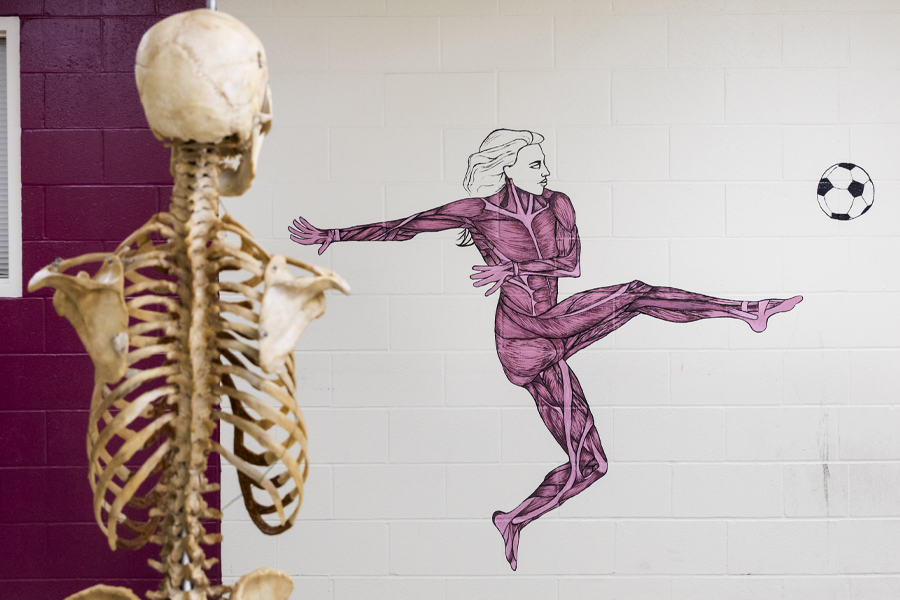

On a formerly blank and boring concrete-block wall in the Florida State University College of Medicine’s anatomy lab, a soccer player perpetually poses in mid-kick. At first glance she appears to be wearing an elaborately patterned bodysuit. Then you see that her body is the suit. She’s wearing nothing but muscle.

She’s right at home in the anatomy lab, where students learn about the mysteries that lie beneath the skin thanks to cadavers that come to the medical school through the Willed Body Program organized by the Anatomical Board of the State of Florida. Typically the students are studying to become doctors or physician assistants. But each semester for the past two years, a handful of art students have come to the lab to explore those same mysteries. Reverently, bundled up against the chill of the lab, they sit and sketch a model who never moves.

Some of these students may become medical illustrators. Whatever career path they follow, they’re grateful to the people who donated their bodies to science — and to art.

Likewise, they’re grateful to the FSU anatomists. Last semester, they began creating murals as thank-you gifts.

“Their work is amazing,” said Eric Laywell, director of the anatomy lab. “Early on, as I was watching them draw, I started thinking about how great it would be to have some of these drawings on our walls down here, to make it a little less institutional.”

Austin Yorke, the Department of Art adjunct instructor who proposed this collaboration, is delighted with the way it has turned out.

“It’s an incredible gift to be able to come down here,” said Yorke, who teaches Figure Drawing 1 and 2. “The entire anatomy-lab team has been giving their expertise to my students. The murals are just our way to try to give back a little bit.”

Yorke heard of a similar collaboration at another school and, feeling inspired, made a cold call to the College of Medicine.

“I was immediately interested,” Laywell said, though it took two years to get the necessary approvals. “I think our cadavers should be used as much as possible for education. That’s why these people donated their bodies. So the more opportunities for legitimate education, the better.”

The key word is “legitimate.” The anatomy lab is sacred space.

“I don’t want people to think that simple curiosity is enough to get you in here, because that is not why people donate their bodies,” Laywell said. “But when it’s a legitimate educational purpose, I love those collaborations — especially when it’s between colleges. For two years, we’ve been hosting these art students. They come in each semester, maybe two or three times, and see the cadavers in various degrees of dissection.”

Yorke said he has seen an evolution in the way his students draw the human body.

“They begin with something that’s got a nice sort of aesthetic quality to the figure, nice line work, the proportions are OK,” he said. “But after coming here, they have the angularity and the smoothness of the body. They start to have an actual spatial position. They start to think about the gentle turning of bones and how they address them. From my perspective, it’s been an incredible benefit to my students. I don’t think it could be replicated any other way, honestly.”

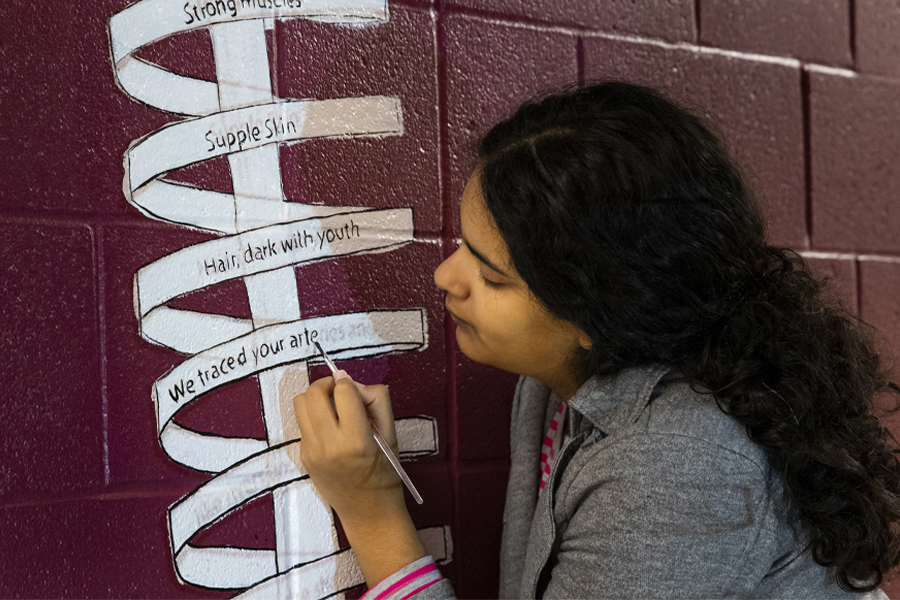

Melissa Gonzalez-Lopez valued the experience so much that, even though she completed the class in the spring, she came back in the fall — on weekends, mostly — to create her mural.

“It’s a unique opportunity that not everyone has the chance to be part of — learning what’s beneath the skin that we draw,” she said. “In the classroom, all that you can draw or paint is what you can see. Here you learn about what actually makes that shape.”

For her mural, she found a poem that thanks the families of the donors.

Brandon Garcia, a Figure 1 student, was excited when he heard of the anatomy opportunity.

“This is an experience I only read about in the textbooks with the Renaissance masters,” said Garcia, whose mural depicts three versions of a human hand: skeletal, circulatory and nervous systems.

When asked to describe how drawing a human model differs from drawing a human cadaver, he used a car analogy: “It’s like drawing what a car would look like and then drawing the inside of the engine. The engine is so complex. How is this facial expression forming? How is this arm moving? How is this affecting the legs and lower back?”

Both Laywell and Yorke said they’d love to see this collaboration expand, someday, into a graduate program for medical illustrators. But that’s just in the idea phase, for the distant future. Meanwhile, there’s still plenty of room for new murals.

To find out more about the Willed Body Program: https://med.fsu.edu/giving/willed-body-program.