A research team in the Department of Scientific Computing has expanded a 1950s math game and turned it into a project that helps undergraduate students practice and grow their skills.

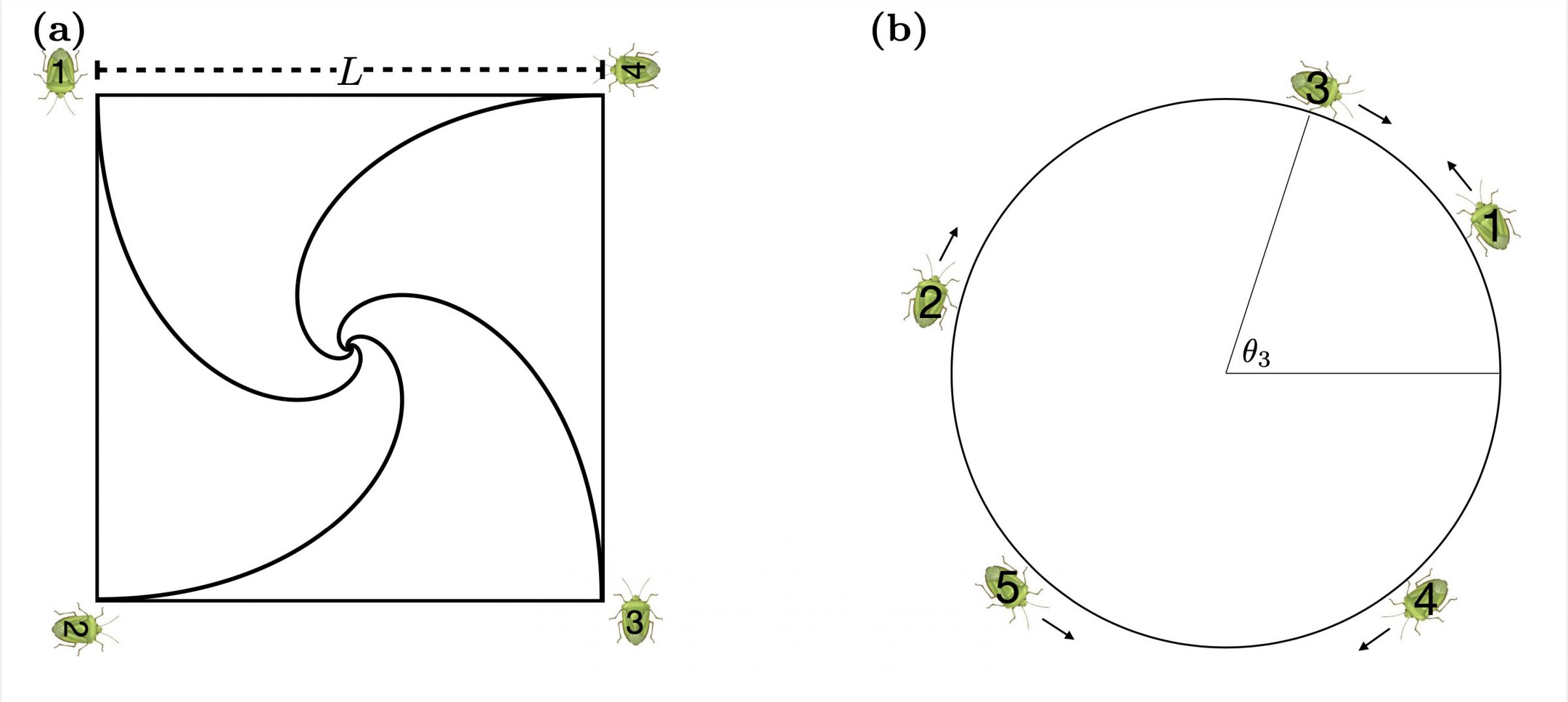

Bryan Quaife, associate professor in the Department of Scientific Computing and faculty associate of the Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Institute, based the work on Martin Gardner’s 1957 puzzle “Four Bugs on a Square.” In the original problem, one bug starts at each corner of an imaginary square and moves toward the one ahead of it at the same speed. Their paths form matching spirals that curve inward until they meet at a single point.

“That problem appeared straightforward,” said undergraduate researcher Josh Briley. “It was just a brain teaser in a magazine, and Gardner published the solution in the next issue.”

Quaife and Briley’s new paper, “N Bugs on a Circle,” changes the setup in fundamental ways. The bugs are no longer placed at abstract corner points. Instead, they begin at random positions on a physical circle and are restricted to move along its perimeter, so they cannot spiral inward. The system can also involve any number of bugs, not just four.

Removing the spiral behavior and confining the bugs to a circular track leads to new dynamics and more complex patterns. Quaife developed the project to give undergraduate students a chance to apply computing and mathematical skills to a problem with simple rules but surprising behavior. Several students contributed over the years, but the project gained momentum when Briley joined.

“I’d tried three or four times to make progress with undergrads, but we never had someone who could stay with it long enough to see it through to publication,” Quaife said. “When Josh and I started working together, the results developed quickly and turned out to be worth publishing.”

When the bugs start at random positions on the circle, each one moves along the perimeter toward the specific bug it is assigned to pursue, a direction set at the beginning of the problem. The team found that the system has three possible long-term behaviors, known as “end states.”

One possible state occurs when the bugs split into two groups on opposite sides of the circle. This configuration is mathematically unstable and does not appear when the starting positions are random. The two stable outcomes are:

- The cycle state, where the bugs fall into an endless chase and never meet, and

- Coalescence, where all bugs eventually arrive at the same point on the circle.

“For large numbers of bugs, the cycle state becomes the most likely outcome,” Quaife said. “The probability that the bugs coalesce is proportional to one over the square root of the number of bugs. So, with 100 bugs, they coalesce only about one out of every ten trials.”

This project is not aimed at solving a real-world problem. Quaife describes it as “recreational math” that helps students turn theory into practice.

Briley said many math and computing students struggle to see how classroom tools relate to actual research. This project showed him how ideas evolve through experimentation, analysis and writing.

“In your classes, you build this toolbox, but sometimes you think, ‘I have all these tools, but nothing to use them on,’” Briley said. “This was a chance to use what I’d learned while also understanding the publication process.”

Quaife noted that moving from an imaginary square to a physical circle opens the door to even more possibilities. Future versions of the project may look at how the bugs behave on other curved surfaces, such as a sphere or a Möbius strip.

Quaife and Briley said they are grateful for the support of the Department of Scientific Computing, which helped them bring the project to publication.

To learn more about the Department of Scientific Computing, visit www.sc.fsu.edu.