Physicists who do research at the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory at The Florida State University got a brand new, high-tech toy for the holidays — a world-record magnet.

Engineers and technicians in late December completed testing of a 36-tesla magnet. (Tesla is a measure of magnetic-field strength; the new magnet is more than 1,200 times stronger than a typical refrigerator magnet.) This achievement reestablishes the magnet lab as the world-record holder for the highest-field “resistive” magnet — a type of electromagnet that uses electricity to generate high magnetic fields. The new magnet — actually an upgrade to an existing one — bests the previous record of 35 tesla, jointly held by the magnet lab and the Grenoble High Magnetic Field Laboratory in France.

“This latest world record is a credit to the ingenuity of the magnet lab’s engineers,” said Nathanael Fortune, chairman of the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory’s User Committee and an associate professor of physics at Smith College in Massachusetts. “The magnet lab’s competitive edge in science and technology depends on continuous enhancements to the lab’s facilities, and users will be thrilled to reach higher fields without increasing the amount of electric power required to get there.”

Engineers at the magnet lab are driven to push magnetic fields as high as possible: They never stop fine-tuning, tinkering and rethinking their magnet designs. This explains why the laboratory holds numerous records — 13 at last count — for strength of field and other key measures of high-magnetic-field research.

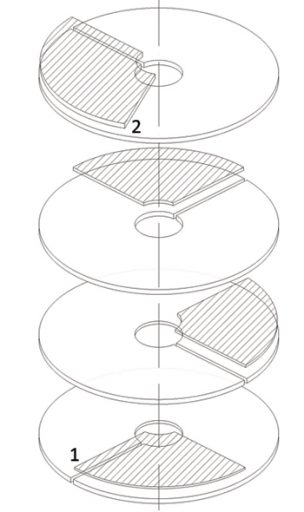

Resistive magnets are built in-house at the magnet lab using so-called Florida Bitter technology pioneered by researchers there. Circular plates of copper sheet metal are stamped with cooling holes; insulators with the same pattern are placed between the plates and stacked to make a coil. Voltage is then run across the coil and current flows to make a magnetic field in the center. Because of the limits of available materials (both to conduct current and to minimize stress on the coils), engineers were stuck at 35 tesla for about four years.

But magnet lab engineers discovered that by adjusting the stacking pattern of the Bitter plates, they could increase the magnetic field without increasing stress on the coils. This cost-neutral modification means a higher magnetic field can be created using the same amount of power, 20 megawatts. By comparison, the magnet at the Grenoble High Magnetic Field Laboratory achieves its 35 tesla using 22.5 megawatts of power.

The 36-tesla magnet, which has a 32-millimeter (1.25-inch) experimental space, will be used primarily for physics and materials science research.

Jingping Chen, manager of the resistive magnet program at the magnet lab, said the upgrade of the magnet is just a start, and that major upgrades are planned for many of the resistive magnets at the laboratory.

“We believe this magnet has the potential to reach even higher fields,” Chen said. “We plan to upgrade our other 35-tesla magnet this year as well. And our wider-bore, 31-tesla magnets will be upgraded to around 33 tesla — which will be a new record in the 50-millimeter (1.97-inch) category.”

The National High Magnetic Field Laboratory develops and operates state-of-the-art, high-magnetic-field facilities that faculty and visiting scientists and engineers use for research. The laboratory is sponsored by the National Science Foundation and the state of Florida. To learn more, visit www.magnet.fsu.edu.