On June 5, 1947, as Europe sat smoldering in the wake of World War II, U.S. Secretary of State George C. Marshall rose to address a Harvard University convocation. During his remarks, Marshall outlined the need for an international cooperative plan for European recovery, drafted by participating European nations and buttressed by “friendly advice” and robust financial support from the United States.

In April 1948, President Harry S. Truman signed the European Recovery Program into law. Seventy years later, the initiative, known popularly as the Marshall Plan, is still celebrated for its instrumental role in catalyzing the resurgence of Western Europe and containing the spread of Soviet-style communism throughout the continent.

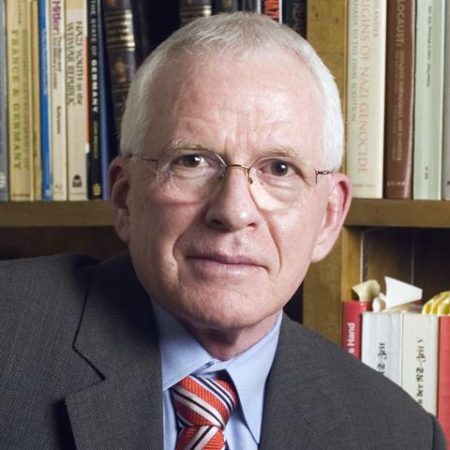

“It was enough to get the wheels turning again,” said Florida State University’s Earl Ray Beck Professor of History Robert Gellately, an expert on postwar Europe. “Europe already had an advanced infrastructure and an educated population — and it was psychologically ready to work. Given the hope of the plan and a free vote, no nation opted for communism.”

As part of the program, the United States provided between $10 billion and $20 billion in aid aimed at stimulating European industry and establishing viable markets for American goods.

“For context, the U.S. budget was $224 billion in 1948,” Gellately said. “If today the American contribution sounds modest, it was in fact considerable.”

Originally, the plan included terms that would have provided aid to the beleaguered Soviet Union and its equally desperate Eastern European satellite states. However, Joseph Stalin and the Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov were wary of the economic and political influence such a program might confer upon the United States. They worried an American-backed European recovery plan would diminish Soviet geopolitical domination and threaten the broader project of European communism.

Ultimately, Stalin rejected the proposal and forbade Eastern European countries such as Poland and Czechoslovakia from participating as well.

“Stalin might have had the opportunity to save the world from the Cold War and the needless expenses and loss of life that went with it,” Gellately said. “He refused in part because if the United States provided funding, it would have wanted inspectors in the recipient nations to ensure that money was spent on ‘butter’ and not ‘guns.’ Maybe some cold warriors in Washington quietly cheered when he turned down the deal, but it was his choice.”

British and French officials, on the other hand, were far more receptive of American support, with British Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin remarking that “it seemed to bring hope where there was none. The generosity of it was beyond our belief.”

While there is some debate as to the precise degree to which the Marshall Plan drove postwar economic recovery in Europe, most agree that it played a critical part in facilitating a period of dramatic growth. Industrial activity was rejuvenated, agricultural production boomed and the stage was set for a political stability among Western European nations that would persist throughout the 20th century.

In the succeeding years, George C. Marshall was hailed for his part in bringing about this era of resurgent prosperity.

“Marshall said that ‘our policy is not directed at or against any country or doctrine but against hunger, poverty, desperation and chaos,’” Gellately said. “He deservedly won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1953 for getting the right answer at the right time.”

Professor Robert Gellately has written and edited a number of books on World War II and postwar Europe, including his most recent work, “Stalin’s Curse: Battling for Communism in War and Cold War.” To arrange an interview, contact rgellately@fsu.edu.