In the midst of an eventful decade for the United States, 1968 proved to be one of the most tumultuous years in history. With the deaths of Martin Luther King Jr. (April 4, 1968) and Robert F. Kennedy (June 5, 1968) occurring only two months apart, the civil rights movement experienced a drastic shift.

As our country commemorates the 50th anniversary of these events, Florida State University’s Davis Houck, the Fannie Lou Hamer Professor of Communication, reflects upon the significance of 1968 and the untimely deaths of these two prominent American figures.

Houck is the architect of FSU’s Emmett Till Archive, nationally regarded as the most prominent research collection on the life and murder of Emmett Till. He is also helping to guide the production of a new documentary and curriculum about civil rights activist Fannie Lou Hamer. Houck has teamed up with Tougaloo College in Mississippi and the Kellogg Foundation on the film “Fannie Lou Hamer’s America” and the corresponding civil rights K-12 curriculum, “Find Your Voice.”

As an expert on the American civil rights movement, war rhetoric, propaganda and media campaigns, Houck can also discuss presidential rhetoric, political advertising, news coverage and speech making.

Houck shared his thoughts on the events of 1968 and their significance.

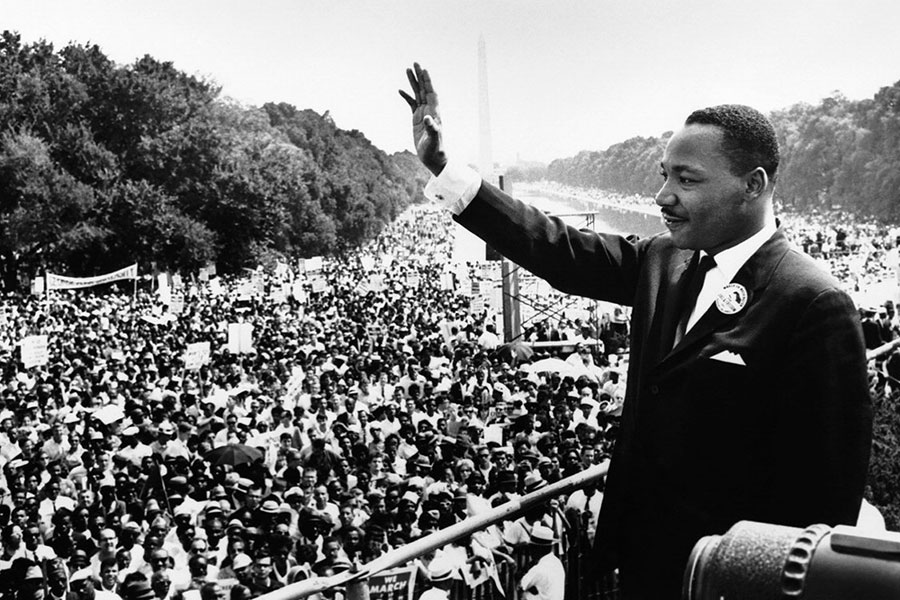

Could you reflect on the assassinations of two major political figures, Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy, and the relevance they still hold today, nearly 50 years later?

Well, they both died so young and were taken in an instant — so close apart with only two months in between their deaths. It shocked the country. Keep in mind, John F. Kennedy had just been shot a few years prior. It sowed a lot of anger between Democrats, considering Robert Kennedy was set to win the Democratic nomination. A lot of the civil rights activists who were allied with Martin Luther King Jr. also started aligning themselves with Kennedy. John Lewis was devastated because that was going to be his guy – that was the man to carry out the civil rights revolution. When King was assassinated, we didn’t have any video, just still images. Bobby Kennedy delivered the news that MLK was assassinated — he was almost like a spokesperson. You could argue that with the assassination of King, you had the full flowering of black power.

Could you elaborate on how this led to the transition to the black power movement?

It was just further proof of the argument that “here’s King, the guy who preaches nonviolence. He’s the reasonable one. You keep murdering us, and because of how we’re being treated we’re not going to do traditional politics in the Democratic party anymore.” It was the final straw and promoted the mentality of “we can’t work within the establishment, we tried but we couldn’t do it,” that many civil rights leaders at the time held. It’s what caused the splintering of the coalition of civil rights activists in 1968.

How did the civil rights movement splinter after the assassinations?

It caused further radicalization, with one part of the splinter becoming the black power movement and the other still being very invested in the Democratic Party and trying to do work within it and the system. It had a little bit of success, but not a ton. This included the formation of the Black Panther Party in Oakland. That fragmentation led to very different political coalitions, which trickled down to local politics rather than to a national constituency.

What effect did this have on the anti-war sentiment many Americans held at the time?

Eventually, a lot of the student nonviolent organizations transitioned from civil rights to anti-war movements. For example, Fannie Lou Hamer transitioned from being a voting rights activist to following King’s mission to pivoting and coming out as anti-war. This is where you see the radicalization of the black athlete, following Muhammad Ali’s lead.

Do we still feel the effects of what occurred that year today? How so?

We should remember that in 1968 Richard Nixon resurrected his foundering political career on the back of television. That medium, and lots of advisers — including the late Roger Ailes, who went on to head up Fox News — was weaponized for arguably the first time. We would do well to remember that the candidates did not debate that year — Nixon having learned his lesson perhaps from 1960. He could exert far more control of his message in other settings.