A dress with optical illusion patterns such as stripes or color blocking can alter how women see their bodies, according to a new study by a Florida State University researcher.

“The goal of this research study was to investigate whether women experience increase body satisfaction through clothing, specifically through optical illusion garments,” said Jessica Ridgway, assistant professor of Retail, Merchandising and Product Development.

Ridgway designed the study so that women could see a an avatar of themselves wearing optical illusion dresses that were designed to make the body appear to be an hourglass shape, which has often been thought of as the ideal shape for women. Ridgway found that participants believed that wearing these items had a positive effect on how they perceived their shape and increased their body satisfaction.

The research, published in Clothing and Textiles Research Journal, and has implications for retailers and designers who may find that incorporating some of these designs will lead to a better shopping experience for their female customers.

“Several retail designers use optical illusions in their clothing,” Ridgway said. “Some of the illusions are well executed and create a flattering effect and some simply do not work well with the body shape of the wearer. I really wanted to understand what these garments do for women from a psychological perspective.”

In this study, Ridgway used a TC2 Body Scanner to collect body measurements of 21 participants. Ridgway used the bust, waist, hip and high hip body measurements to classify participants into one of nine body shape categories. Ridgway then narrowed the group to women who had the three most common body shapes found for women — hourglass, spoon and rectangle. Out of the 21 women scanned, 15 fell into these categories.

Women with an hourglass shape typically have a narrow waist with wider shoulders and hips. The rectangle tends to have similar measurements in the shoulder, waist and hips. And the spoon shape carries most of the weight below the waist in the hips and backside.

Ridgway then created a custom avatar for each of the 15 women who fell into those categories based on their body scans and used software to give the avatar the facial features of each participant. The goal was for the avatar to look as similar as possible to the participant, she said.

“This was important to me because I wanted them to feel like they were looking at themselves,” she said.

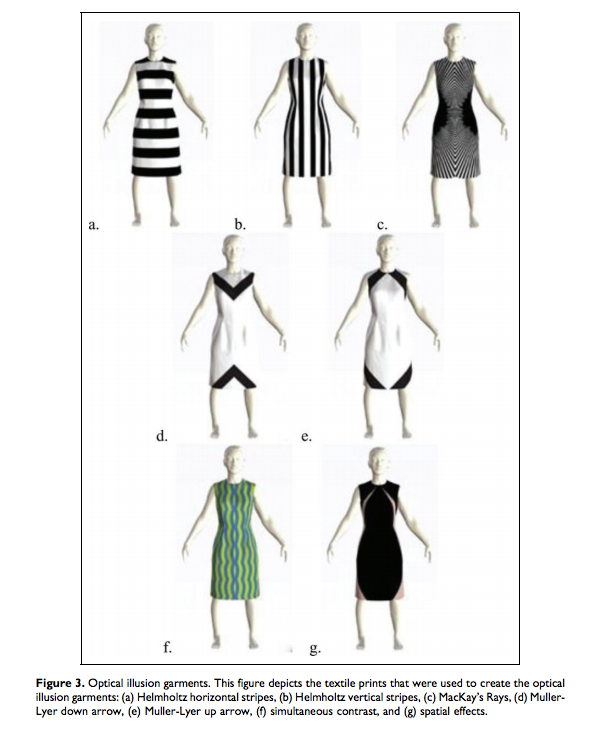

Ridgway showed the women their avatar wearing seven different shift dresses that had optical illusion designs. Ridgway designed each of the optical illusion dresses for the purpose of this study, but played on established illusions such as vertical and horizontal stripes or radial rays.

While viewing their avatar in each different type of dress, the participants answered a series of questions including how they would describe their bodies and how they felt they looked with each dress. Since the optical illusion designs were created to give the illusion of a more hourglass figure, Ridgway noted that people who already have an hourglass shape were the most indifferent to the change of clothing.

Women with a rectangle body shape reacted the most strongly to changes in the clothing, though these participants were divided on the designs that they liked the best. Mostly, they liked designs that they felt defined their waists or made them appear curvier.

Women with the spoon shape fell somewhere in the middle, but were more pleased with their appearance when depicted in garments that emphasized their bust and shoulders, which balanced out their proportions, Ridgway said.

Ridgway said this was an exploratory study to look at the methods for the application of technology in the digital design process and the use of avatars. She is working on a follow-up study that examines additional illusions and the impact of avatar use. Ridgway’s overall research goal is to better understand how dress affects body image and women’s overall psychological health.

Ridgway’s co-authors are Jean Parsons from University of Missouri and Myung Hee Sohn from California State University Long Beach.