Over the past several decades, the Arctic has begun to show signs of significant ecological upheaval. The rate of warming in the Arctic is nearly twice the global average, and those changes are triggering a cascade of destabilizing environmental effects. Ice is melting, permafrost is thawing, and experts say fires in Arctic forests are as damaging as they’ve been in 10,000 years.

But new research suggests that the same factors driving the Arctic’s changing climate are fueling a geological response that could play a small part in counteracting those changes’ malign effects.

In a study published in the journal Environmental Science & Technology, researchers from Florida State University report that, in two major Arctic rivers, 40 years of climate change seem to have fortified a natural process that consumes and stores atmospheric carbon dioxide.

The process of interest to researchers was the production of riverine alkalinity, or the ability of river water to resist changes that would make it more acidic. Alkalinity is produced when carbon dioxide dissolved in rainwater weathers rock surfaces. As the rocks are weathered, the carbon atom contained in carbon dioxide is transformed from a gas in the atmosphere into a bicarbonate ion that can be geologically stored for millennia.

In general, the more alkalinity detected in a given waterway, the more carbon dioxide was withdrawn from the atmosphere.

“The production of alkalinity is a natural way that the Earth recycles atmospheric carbon dioxide,” said study lead author Travis Drake, a doctoral candidate in FSU’s Department of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Science.

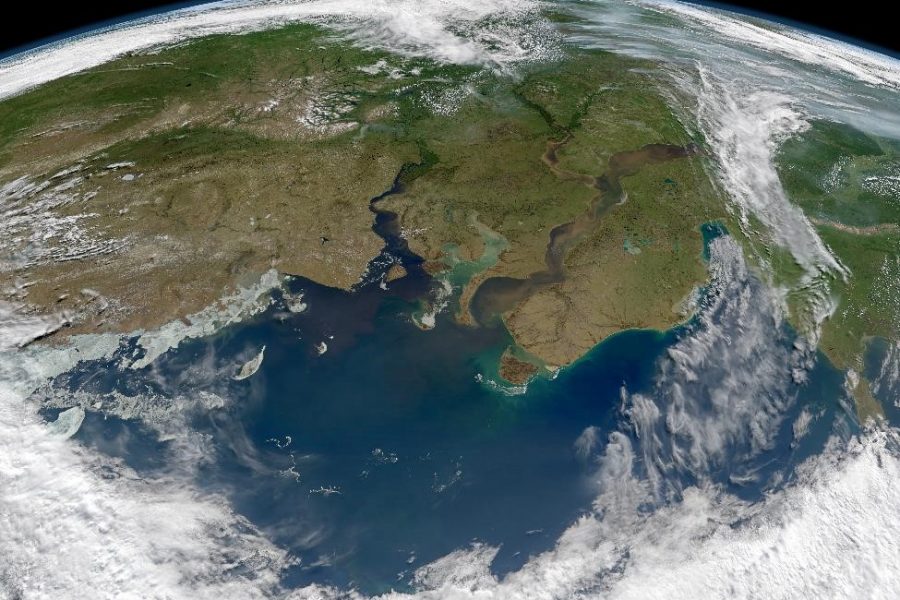

The production of alkalinity constitutes a carbon dioxide “sink,” a system that works in opposition to natural and anthropogenic carbon dioxide emission. The researchers set out to determine how changing human activity and the dramatic shifts in Arctic climate might be affecting alkalinity production in two of the region’s largest rivers, the Ob’ and the Yenisei.

There were straightforward ways of sampling alkalinity in the modern rivers, but for historical measurements, the team relied on reams of decades-old biomonitoring data.

“Since there are many changes underway in the Arctic as a result of climate change and other anthropogenic activity, we hypothesized that the production of alkalinity may have also changed over time,” Drake said. “Through collaboration with our Russian colleagues, we were able to recover a historic alkalinity dataset dating back to the Soviet era.”

After parsing the data and comparing historical alkalinity rates with contemporary measurements, the researchers’ suspicions were confirmed. Not only had alkalinity increased for both the Yenisei and Ob’ rivers, but the rates had skyrocketed a remarkable 185 and 134 percent respectively over the 40-year interval — two figures that dwarf the rates of increase in similarly large rivers like the Mississippi (59 percent over the past 47 years).

Possible causes for the considerable alkalinity increases are manifold. Thawing permafrost, increased water flows, exposure of unweathered mineral surfaces, changes in acid deposition from human industry and carbon dioxide fertilization of Arctic plant life are all potential pieces of this unexpected puzzle.

But the upshot is simple: In these rivers that carve thousands of miles through the harsh Arctic landscape, human activity seems to be triggering a pronounced reaction.

“If climate change is causing an increase in alkalinity production in the Arctic, it could be acting as slight negative feedback to warming, which is a good thing,” Drake said.

While escalating alkalinity won’t approach the magnitude of response required to counterbalance anthropogenic carbon dioxide emissions, researchers said these findings illustrate the dynamic way Earth systems react to extreme climate shifts.

“We still very much have to worry about the alarming rate at which CO2 is increasing in our atmosphere, but this highlights the complexity and somewhat homeostatic dynamics of the global carbon cycle,” Drake said.

FSU Associate Professor of Oceanography Robert Spencer contributed to this study, along with Suzanne Tank from the University of Alberta, Alexander Zhulidov and Tatiana Gurtovaya from the South Russia Centre for Preparation and Implementation of International Projects and Robert Holmes from the Woods Hole Research Center. The research was supported by the National Science Foundation.