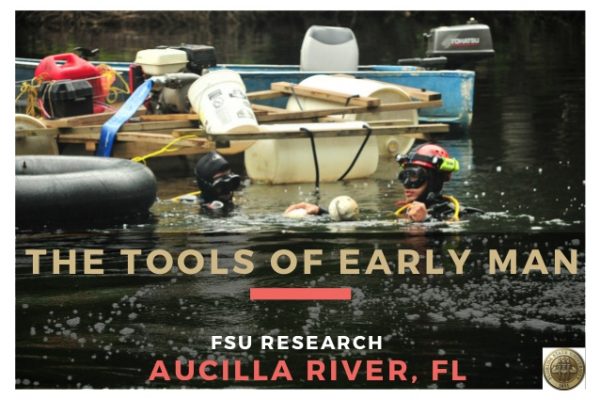

The discovery of stone tools alongside mastodon bones in a Florida river shows that humans settled the southeastern United States as much as 1,500 years earlier than scientists previously believed, according to a research team led by a Florida State University professor.

This site on the Aucilla River — about 45 minutes from Tallahassee — is now the oldest known site of human life in the southeastern United States. It dates back 14,550 years.

“This is a big deal,” said Florida State University Assistant Professor of Anthropology Jessi Halligan. “There were people here. So how did they live? This has opened up a whole new line of inquiry for us as scientists as we try to understand the settlement of the Americas.”

There is a cluster of sites all over North America that date to around 13,200 years old, but there are only about five in all of North and South America that are older.

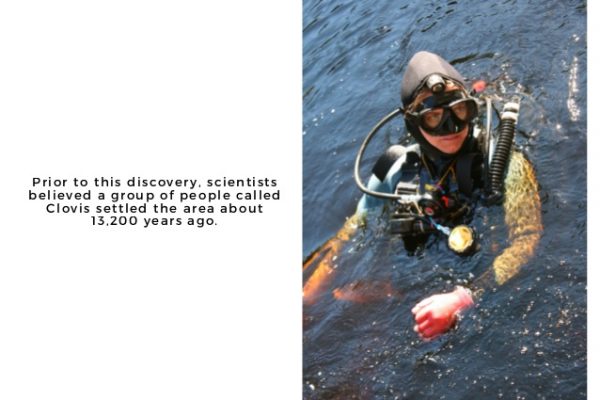

Halligan and her colleagues, including Michael Waters from Texas A&M University and Daniel Fisher from University of Michigan, excavated what’s called the Page-Ladson site, which is located about 30 feet underwater in a sinkhole in the Aucilla River. The site was named after Buddy Page, a diver who first brought the site to the attention of archaeologists in the 1980s, and the Ladson family, which owns the property.

Halligan’s research was published today (May 13) in the academic journal Science Advances.

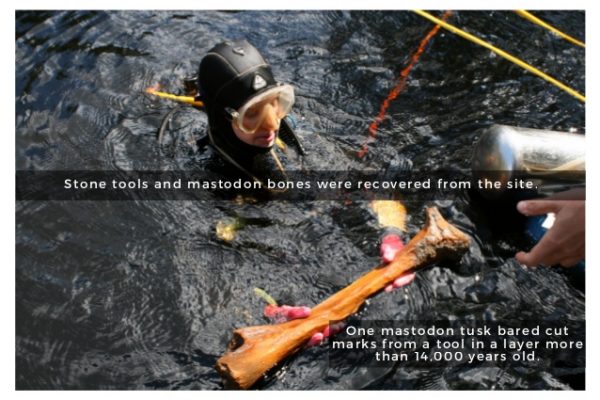

In the 1980s and 1990s, researchers James Dunbar and David Webb investigated the site and retrieved several stone tools and a mastodon tusk with cut marks from a tool in a layer more than 14,000 years old. However, the findings received little attention because they were considered too old to be real and questionable because they were found underwater.

Waters and Halligan, who is a diver, had maintained an interest in the site and believed that it was worth another look. Between 2012 and 2014, divers, including Dunbar, excavated stone tools and bones of extinct animals.

They found a biface — a knife with sharp edges on both sides that is used for cutting and butchering animals — as well as other tools. Fisher, a vertebrate paleontologist, also took another look at the mastodon tusk that Dunbar had retrieved during the earlier excavations and found it displayed obvious signs of cutting created to remove the tusk from the skull.

The tusk may have been removed to gain access to edible tissue at its base, Fisher said.

“Each tusk this size would have had more than 15 pounds of tender, nutritious tissue in its pulp cavity, and that would certainly have been of value,” he said.

Another possible reason to extract a tusk is that ancient humans who lived in this same area are known to have used ivory to make weapons, he added.

Using the latest radiocarbon dating techniques, researchers found all artifacts dated about 14,550 years ago. Prior to this discovery, scientists believed a group of people called Clovis — considered among the first inhabitants of the Americas —settled the area about 13,200 years ago.

“The new discoveries at Page-Ladson show that people were living in the Gulf Coast area much earlier than believed,” said Waters, director of Texas A&M’s Center for the Study of the First Americans.

Added Halligan: “It’s pretty exciting. We thought we knew the answers to how and when we got here, but now the story is changing.”

Other researchers on the study are Angelina Perrotti and David Carlson from Texas A&M, Ivy Owens from the University of Cambridge, Joshua Feinberg and Mark Bourne from the University of Minnesota, Brendan Fenerty from the University of Arizona, Barbara Winsborough with the Texas State Museum, and Thomas Stafford Jr. from Stafford Research Laboratories in Colorado.

The research was funded by the Elfrieda Frank Foundation, the National Geographic Society and the North Star Archaeological Research Program and Chair in First American Studies of Texas A&M University. It was also supported by the Ladson family, which allowed researchers to perform multiple excavations on their property over the past several years.