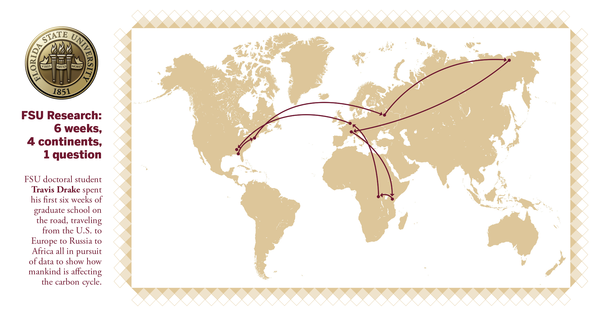

Six Weeks. Four Continents. One Question.

How is mankind affecting the global carbon cycle?

That was Travis Drake’s introduction to Florida State University this fall. The new doctoral student, studying with Assistant Professor in the Department of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Science, Robert Spencer, spent his first few weeks with some serious on-the-job training.

Spencer’s research focus is on how human impacts such as climate change, land-use change and combustion of fossil fuels are affecting the carbon cycle, particularly the movement of carbon between reservoirs. His graduate students are a key part of that work, traveling with him to collect and process samples from all over the world.

That required Drake, who moved to Tallahassee from Colorado in August, to prepare for a whirlwind tour. His total flight plan involved 16 different airports as he made his way from Tallahassee to remote field sites in Siberia, back to Europe to drop off collected samples, and then on to Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo for more field work. Then, he traveled back through Europe to Tallahassee.

“I can’t imagine a better start to a Ph.D. program,” Drake said. “I arrived in Tallahassee a week before this trip so I had to scramble to become a Florida resident, enroll as a student, prepare all my sampling equipment, and pack for both cold weather — Siberia — and the tropics — the Congo. But opportunities like this are why I came to FSU. It’s a huge privilege to travel to remote field sites and to be a part of Dr. Spencer’s lab. There are a lot of important unanswered questions in the field of biogeochemistry and many of them require a global perspective.”

These field expeditions form the backbone of Spencer’s lab. To understand how humans are affecting large carbon stores such as permafrost soils in the Arctic and the tropical forests, scientists need to be on the ground in these regions.

“Conducting scientific research in some of these remote regions presents a unique challenge, but the questions we are posing have ramifications for us in Florida,” Spencer said. “Permafrost soils in Siberia may have stored carbon for 30,000 years, but now as the region thaws, that carbon is liberated and bacteria converts it to carbon dioxide. As that then returns to the atmosphere, it is clear that what happens in some of these distant regions does not stay there.”

In Siberia, Spencer and Drake hope to show how much permafrost carbon is being converted to carbon dioxide by bacteria in rivers and streams and assess how much of this greenhouse gas ultimately returns to the atmosphere, fueling further warming.

In the Congo, they are working to establish new field sites in collaboration with local scientists from the city of Bukavu to gauge how conversion of pristine tropical forests to agriculture are affecting soil carbon stocks with ramifications for soil fertility in the future.

“This fledgling project in the Congo also provides Dr. Spencer and I the tremendous opportunity to work alongside Congolese scientists and students, and to relate some of the very positive developments occurring in the region back to our community at FSU,” Drake said.