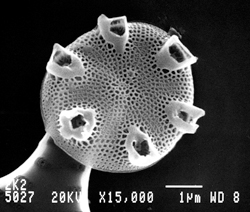

Remarkable for their exquisite, glass-like cell walls in every imaginable 3-D shape and pattern — and important for their role as bio-indicators of water quality — diatoms are the predominant group of microscopic, single-celled algae at the base of the aquatic food chain.

For 35 million years or more the prolific plants have thrived in every freshwater, brackish and marine environment on Earth. Scientists estimate the number of diatom species at anywhere from 10,000 to 10 million. Given the nearly impossible task of discerning minuscule cell-wall differences among them all using commonly available light-microscopy techniques, only a fraction have been isolated and positively identified.

Now, make that a fraction plus one.

Using a state-of-the-art electron microscope at Florida State University, FSU biologist Akshinthala K.S.K. Prasad recently identified a new diatom genus and species, and he didn’t have to look far to find it. He discovered the novel diatom in a seven-year-old sample of material that a colleague had collected from the St. Johns River in Northeast Florida’s Putnam County. Consultations with international diatom experts helped to confirm that what he was seeing was something entirely new at the genus level and undocumented at the species level.

“Our discovery is both exciting and humbling because it underscores what we still don’t know about our aquatic environment,” Prasad said.

“The St. Johns is not in some far-off land,” he said. “It is a major medium-sized river in the southeastern United States and the largest river in Florida in both length and magnitude of its drainage basin. Its biology has been monitored by a variety of groups for a number of years.

“And yet, suddenly, in large numbers, a previously unrecognized plant form appears.”

And not just any form, notes Prasad. This new diatom is part of an old plant family that dates back to the Mesozoic Era and boasts one of the Earth’s most abundant, diverse and biogeochemically active lineages of photosynthetic eukaryotes — organisms whose cells contain complex structures enclosed in membranes.

In collaboration with FSU doctoral alumnus James A. Nienow, now a biology professor at Valdosta (Ga.) State University, Prasad has named the newfound diatom Livingstonia palatkaensis. The designation honors Prasad’s longtime FSU research colleague Professor Emeritus Robert J. Livingston, an ecologist whose grant funded an earlier study that produced the key St. Johns River sample. The name also recognizes Palatka, Fla., the town near the sample collection site.

Prasad and Nienow describe the identification of Livingstonia palatkaensis in a paper published in the journal Phycologia.

Both as fossils and living organisms, diatoms are attracting increasing attention from science and industry. The tiny plants reflect declining water quality, sometimes doing so with algal blooms known as red tides. They serve as markers during oil exploration, and in forensic investigations. They are used in analyzing various ecological problems such as acidification and climate change, both in freshwater and marine environments.

Meanwhile, diatoms are captivating casual observers and scientists alike thanks to 21st-century imaging techniques that reveal beautifully sculpted, highly ornamented architectural designs in never-before-seen detail.

“In these days of rapid industrial changes and inevitable technological advancement,” said Prasad, “it is amazing to realize that a large group of single-celled plants have been living in glass houses for at least 35 to 40 million years and still find this a successful mode of existence.”

Visit FSU’s Department of Biological Science website to learn more about Prasad’s research.