Florida State University music and theater students are finding even though their classroom setting is a tad different this semester, the advent of modern technologies has created a tight sense of community and flexible learning environment during the COVID-19 crisis.

Instructors Holly Riley from the College of Music and Jason Paul Tate from the College of Fine Arts’ School of Theatre, are working with students to ensure they receive a unique educational experience, despite the fact they can’t go to live musical or theatrical performances or rehearse with classmates.

Originally, Riley’s courses encouraged students to interact socially by attending local community spaces and performing with local artists as musicians. Now, she has shifted her focus toward digital collaboration and recording techniques, finding success with Zoom during her Irish Ensemble class.

“I mute my class on Zoom and play the melody on fiddle,” she said. “Students listen and each play their own parts. It really creates a sense of community knowing we are all playing the same song even though we are unable to hear one another.”

Instructors and students have increased flexibility as they navigate through this unknown territory.

Riley thinks that in the world that we are living in now, rigidity doesn’t work.

“People are in such wildly different places academically and socially; it is important to adapt with your students,” Riley said. “The funny thing is, in many ways, that has always been the case. Pandemic or no pandemic, our students have always been in different places.”

With in-person teaching, instructors can read body language and get a general feel for the classroom based on the energy of the students. They can tailor how they disseminate information that day. Remote courses are very different, and instructors often find themselves having to come out and ask how students are doing directly.

Now more than ever, it is important for Riley to verbally check in on her students.

“It is interesting to hear about all of the different perspectives and play music through a collective experience,” Riley said. “We are not doing this for the grade anymore, we are doing this because we are all human and we are all going through this together. We are trying to maintain a community.”

“It is interesting to hear about all of the different perspectives and play music through a collective experience.”

— Holly Riley, College of Music

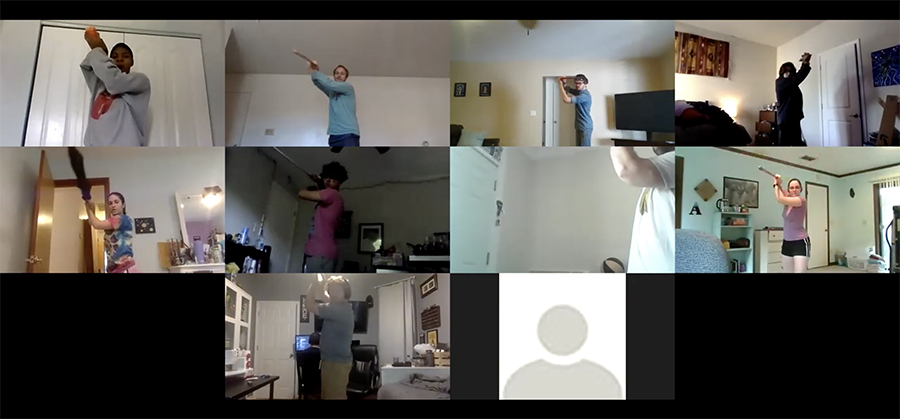

Tate, visiting assistant professor of practice in the School of Theatre, currently teaches three different courses that focus on speech in theater, theatrical movement and stage combat techniques.

He’s found this challenge exciting and full of opportunity. Moving completely online has allowed his students to dive into the practice from a new perspective, though it has required extreme flexibility in how he teaches the courses.

Tate’s Stage Combat class has presented the greatest obstacles to overcome.

“While holding one another ‘en garde’ with swords would certainly hold up to the social distancing recommended guidelines, it makes for a very poor representation of a fight,” Tate said. “Without the expansion and contraction of two bodies in space as they truly attack and defend one another in a way that makes an audience flinch or fear for a character’s life, the fights fall stagnant and lack the capacity to entertain.”

Tate had to totally rethink the course. In the digital classroom space, the learning objectives focus on creating the illusion of violence, while maintaining an underlying structure of consistent and safe nonverbal communication.

“We are also continuing to work on the tools of violent storytelling as they relate to one side of the fight at a time — strong isolations and vocal reactions when defending proper body engagement, targeting and stance when attacking with whatever household sword surrogate we managed to lay our hands on,” Tate said.

For his theatrical speech students, Tate has found that the new learning environment has some benefits. In his prior studio space, Tate only had access to a whiteboard, which slowed down the learning process while he first wrote samples on the board for his students.

By utilizing the mute button through Zoom, his voice students can hear only themselves and not compete with the sounds of others.

“I can address each of them individually and have the others listen if necessary,” Tate said. “They can still observe one another’s face shape and breathing cues on screen. Additionally, I can share my screen and read through sample texts with them.”

This increased individualization of the courses has motivated the students to adapt the coursework to fit their lives, intentions and goals for their futures.

In Tate’s theatrical movement course, he has been quite surprised by the opportunity that the Zoom mediums and change of scenery has offered to students’ work.

“This work is intended to allow the actor to see the world around them as a continual scene partner. This removes the pressure from them to have to be creative all the time and allows them to be the participant in their own experience reacting to the world around them,” Tate said.

Students’ childhood homes or college apartments are rich with memories and experiences that would not normally affect them in the classroom space.

“They have jumped into the forefront of the work, broadening the realm of experience within the whole class as they share work created in these spaces with one another via video,” Tate said.

Tate’s greatest takeaway from this experience has been how much more willing a student is to reach out for help by visiting him during digital office hours than they were when he held hours on campus.

“I may very well continue to offer students that opportunity when appropriate,” Tate said. “It feels as if once they realize you are in fact ready to assist and that those meetings have benefit, the trust and willingness to go further in the classroom often follows.”