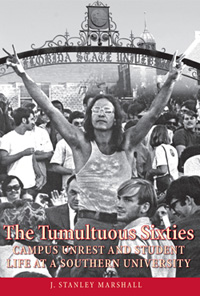

Stan Marshall, president of Florida State University from 1969-76, reports on turbulent years at FSU in his new book, The Tumultuous Sixties: Campus Unrest and Student Life at a Southern University. Marshall is the first to profile a major southern university during a time marked by racial and political tension. Readers journey through events that would shape a university and its future, including the hiring of Bobby Bowden as football coach and the dramatic upheaval of a campus making history.

If the defining event for baby boomers was the Vietnam War and the protest over the draft, then a new book written by a former president of Florida State University should have a wide audience.

The book, Tumultuous Sixties: Campus Unrest and Student Life at a Southern University, has just been released and will be available for purchase via the FSU Alumni Association, which will receive $5 for each copy sold online. The book also can be found at www.stanmarshallbooks.com, Florida State University Bookstore and Bill’s Bookstores.

In the introduction to his book, J. Stanley Marshall, FSU’s president from 1969 through 1976, writes that its primary audience is likely to be "members of the FSU family now and during the time I was president of the university." And it is true that there is much within the book that will bring back memories, both fond and bittersweet, of a pivotal time in the university’s history for those who were there to experience it.

As president of the "Berkeley of the South," Marshall had his work cut out for him. It was a time of great progress but also many challenges as the campus community was torn by demonstrations and faculty dissension, with some professors siding with protesting students against the war. Women’s rights and black students’ rights, campus radicals, sexual permissiveness and drug use were issues of the day. On top of all that, you can add streaking.

As a member of the FSU family for the past 12 years, I read much in "Tumultuous Sixties" that was not only fascinating but also enlightening. However, the connections I made to what Marshall wrote were even more meaningful to me as a baby boomer, a Vietnam veteran, and a beneficiary of the GI Bill and higher education.

For example, as I read his account of one of the more compelling events in FSU history, the "Night of the Bayonets" on March 4, 1969, I found myself reflecting upon what I was doing and thinking when Marshall, as president of FSU, was facing a showdown on campus with the activist group Students for a Democratic Society (SDS).

In his account of that tense evening, Marshall writes that "the situation posed a threat of violence." Indeed, a similar protest a year later at Kent State University escalated into bloodshed as Ohio National Guardsmen shot and killed four students and wounded nine others.

In retrospect, Marshall believes that his policy of "firmness coupled with fairness" was proven correct in that confrontation with the SDS. He enforced an injunction he had obtained under the rule of law in dealing with the students. The result: no violence; no casualties; only arrests.

The "Night of the Bayonets" account took me back to my own thoughts and experiences on a different campus. I think other readers—many outside the FSU family—will find themselves doing the same for many of the incidents Marshall recounts in his book.

As a student at Southern Illinois University, I was majoring in business and "fun" before I volunteered for the draft in May 1966. Most of my fellow students were talking about ways to evade the draft, such as going to Canada. I wanted to get it on, get it over with and reap the educational benefits of the GI Bill.

In March 1968, I had completed serving one year, nine months and 18 days in the U.S. Army, including 11 months and 24 days in Vietnam. I had been a Specialist E-5 (a sergeant), serving in the Army’s 26th General Support Group in Tuy Hoa. I did not see much action, only nearby bombings. Mostly, I saw the aftermath of battles. And one of those experiences made me a lot more serious about the value of life and what I was going to do with mine. It also gave me newfound tolerance for anti-war protestors.

It had happened sometime in February 1968, after the beginning of the Tet Offensive, the political and psychological victory for the North Vietnamese communists that dramatically contradicted optimistic U.S. government claims that the war already had been won.

I was a chaplain’s assistant, and we were called to the Army’s 91st Evacuation Hospital, a nearby, tented compound on the beaches of the South China Sea. The chaplain was there to give last rites. I assisted. The event was my first witnessing of a casualty of war, who I later learned was a 19-year-old Hispanic kid from Los Angeles.

As the chaplain opened the body bag, I saw the young man’s upper body, which had been ripped open from his right shoulder to his left hip. I remember the dried blood around each of the eight to 10 neat bullet holes. The body bag was not opened enough to see the exit wounds, but I knew about the gore of those things.

My mind was overwhelmed by the thought that I was looking at the dead body of someone’s son, and then the more devastating thought: "His parents don’t even know he’s dead yet." I felt helpless, sad and empty. Life became much more precious to me at that moment.

When I returned from Vietnam, there was no welcome for a soldier who had done his duty. There were no ribbons on cars bearing the words "Support the Troops." But I didn’t care. I knew that I had learned some important lessons in Vietnam and that I was now going to use the GI Bill benefits to get as much education as I could.

Eventually, I earned a master’s degree in journalism from Northern Illinois University and was selected for membership by Kappa Tau Alpha, the national journalism scholarship society.

President Marshall’s book made me think of all of this and more.

As I learned from his book, Marshall was criticized for not closing the doors of the university in the wake of the Kent State shootings—as some other universities did—but I believe he made the right decision. It was more important to carry on with the mission of education. I learned a big lesson in 1968 in Vietnam. I learned about the fragility of human life and about the value of an education that I had been taking for granted up until that time.

I also have thought about what Marshall wrote concerning possible student protests of the current war in Iraq. Now college students mostly are protesting military recruiting on college campuses. But if we had other conditions similar to Vietnam—such as a draft—and if we were seeing and hearing the casualty figures nightly on the news, as with the Vietnam War, I believe we would see many protests on college campuses.

I remain confident, however, that it is not inconsistent to support the right to protest and yet insist upon keeping the doors to education open.

I also am confident that many others will find Tumultuous Sixties: Campus Unrest and Student Life at a Southern University just as thought provoking as I did.