A Florida State University and University of Alaska Fairbanks research team has uncovered a new species of duck-billed dinosaur, a 30-foot-long herbivore that endured months of winter darkness and probably experienced snow.

The skeletal remains of the dinosaurs were found in a remote part of Alaska. These dinosaurs were the northernmost dinosaurs known to have ever lived.

“The finding of dinosaurs this far north challenges everything we thought about a dinosaur’s physiology,” said FSU Professor of Biological Science Greg Erickson. “It creates this natural question. How did they survive up here?”

The dinosaur is named Ugrunaaluk kuukpikensis, which means ancient grazer of the Colville River. The remains were found along the Colville River in a geological formation in northern Alaska known as the Prince Creek Formation.

The discovery is detailed in today’s issue of the paleontology journal Acta Palaeontologica Polonica.

“This new study names and brings to life what is now the most completely known species of dinosaur from the Polar Regions,” said Patrick Druckenmiller, Earth sciences curator of the University of Alaska Museum of the North and associate professor of geology at the University of Alaska Fairbanks.

The dig site — the Prince Creek Formation — is a unit of rock that was deposited on an arctic, coastal flood plain about 69 million years ago.

At the time the Prince Creek Formation was deposited, it was located well above the paleo-Arctic Circle, about 80 degrees north latitude. So, the dinosaurs found there lived as far north as land is known to have existed during this time period.

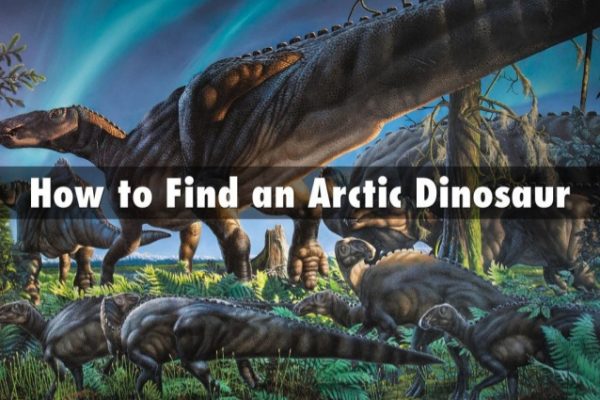

At the time they lived, arctic Alaska was covered in trees because Earth’s climate was much warmer as a whole. But, because it was so far north, the dinosaurs likely contended with months of winter darkness, even if it wasn’t as cold as a modern-day winter. They lived in a world where the average temperature was about 43 degrees Fahrenheit, and they probably saw snow.

“What we’re finding is basically this lost world of dinosaurs with many new forms completely new to science,” Erickson said.

Since the 1980s scientists from the University of Alaska Museum of the North and other collaborative institutions, including Florida State University, have collected more than 9,000 bones from various animals as part of the excavation of the Prince Creek Formation.

The majority of the bones of the Ugrunaaluk kuukpikensis were collected from a single layer of rock called the Liscomb Bonebed. The layer, about 2 to 3 feet thick, contains thousands of bones of primarily this one species of dinosaur. In this particular area, most of the skeletons were from younger or juvenile dinosaurs, about 9 feet long and three feet tall at the hip.

Researchers believe a herd of juveniles was killed suddenly to create this deposit of remains.

Hirotsugu Mori, a former graduate student at UAF, completed a detailed analysis of the bone structure as part of his doctoral dissertation alongside Druckenmiller and Erickson. Their work revealed that the Ugrunaaluk kuukpikensis is most closely related to Edmontosaurus, another type of duck-billed dinosaur that lived roughly 70 million years ago in Alberta, Montana and South Dakota.

But, the combination of features found in these skeletons were not present in Edmontosaurus or in any other species of duck-billed dinosaurs.

In particular, researchers observed that the Ugrunaaluk kuukpikensis had very unique skeletal structures in the area of the skull, especially around the mouth.

“Because many of the bones from our Alaskan species were from younger individuals, a challenge of this study was figuring out if the differences with other hadrosaurs was just because they were young, or if they were really a different species,” Druckenmiller said. “Fortunately, we also had bones from older animals that helped us realize Ugrunaaluk was a totally new animal.”

Druckenmiller worked with an instructor of the Iñupiaq language at the Alaska Native Language Center at University of Alaska Fairbanks to develop a name for the new species that was culturally, anatomically and geographically correct. They wanted to pay tribute to the local tribes who live near the research site.

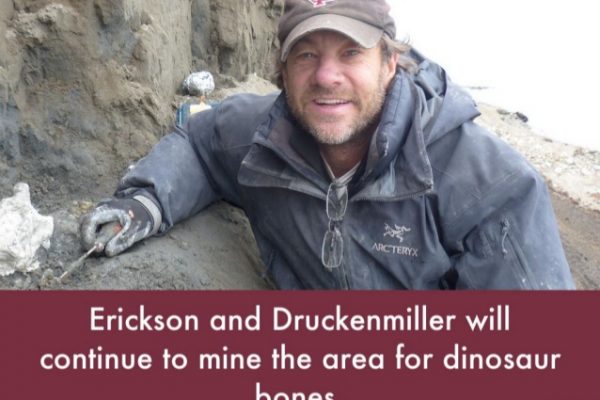

Erickson and Druckenmiller will continue to mine the Prince Creek Formation for additional skeletons. However, accessing the field site is extremely difficult. Besides the frigid weather, they have to use bush planes that are capable of landing on gravel bars and inflatable boats to access the sites and often have to rappel down the side of a cliff to do the digging.

The area is rich with animal skeletons, and they estimate there are at least 13 different species of dinosaur present based on teeth and other remains, plus birds, small mammals and some fish.

They will also delve deeper into how these animals lived and functioned in conditions not typically thought to be amenable to occupation by reptilian dinosaurs.

“Alaska is basically the last frontier,” said Erickson, who is originally from Alaska. “It’s virtually unexplored in terms of vertebrate paleontology. So, we think we’re going to find a lot of new species.”

Three full skeletons of Ugrunaaluk kuukpikensis will be on display at the University of Alaska Museum of the North as well as a new painting of the species by Alaskan artist James Havens.

This research was supported by the National Science Foundation and the Department of Interior’s Bureau of Land Management. The research is also the primary subject of the doctoral thesis completed by Druckenmiller’s former graduate student Hirotsugu Mori, who is now a curator for the Saikai City Board of Education in Japan.