In the shadow of South Australia’s largest mountain range beneath the outback soil lies a fossil record that reveals a rich history of life on Earth.

Fossils found at Nilpena Ediacara National Park preserve a pivotal moment in the history of evolution: the crucial period during which single-celled organisms began to evolve into the planet’s first complex, visible animals.

A new discovery in the area by Scott Evans, assistant professor of geology in the Florida State University Department of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Science, and a multi-institution team of paleontologists has identified an early marine animal from around 555 million years ago. The discovery helps answer how life evolved on Earth.

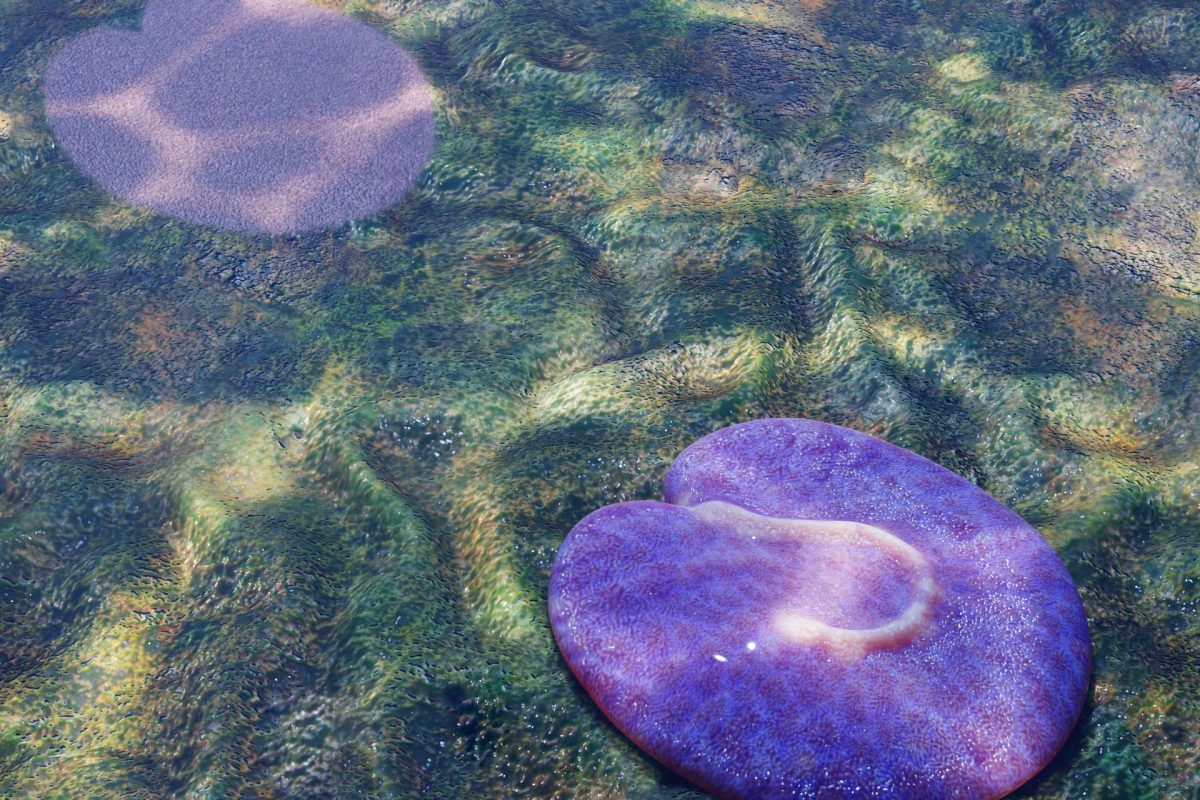

Quaestio simpsonorum is the first animal to show definitive left-right asymmetry, an important sign of evolutionary development. The team’s findings appear in the September issue of Evolution & Development.

“The animal is a little smaller than the size of your palm and has a question-mark shape in the middle of its body that distinguishes between the left and right side,” Evans said. “There aren’t other fossils from this time that have shown this type of organization so definitively. This is especially interesting as this is also one of the first animals that was capable of moving on its own.”

Researchers said Quaestio, pronounced “kways-tee-oh,” behaved like a small marine Roomba vacuum, consuming nutrients from microscopic algae, bacteria and other organisms as it moved along the seafloor. The collection of microbes formed an organic mat, like a layer of slime filled with nutrients on the seafloor, which formed a particular texture preserved in the rock slabs that make up the park’s fossil beds. Researchers discovered distinct Quaestio impressions along with evidence of its trails — known as trace fossils — in this fossilized mat texture.

“One of the most exciting moments when excavating the bed where we found many Quaestio was when we flipped over a rock, brushed it off, and spotted what was obviously a trace fossil behind a Quaestio specimen — a clear sign that the organism was motile; it could move,” said Ian Hughes, a Harvard University organismic and evolutionary biology graduate student and one of the team’s researchers.

The team also includes researchers from the University of California, Riverside, the South Australian Museum and the University of Adelaide, Australia.

Mary Droser, Nilpena’s lead scientist, distinguished professor of geology at UC Riverside and Evans’ former doctoral adviser, has guided this team on digs in the outback for more than 20 years. The project was funded by NASA, the Australian Research Council and the Agouron Institute.

“It’s incredibly insightful in terms of telling us about the unfolding of animal life on Earth,” Droser said. “We’re the only planet that we know of with life, so as we look to find life on other planets, we can go back in time on Earth to see how life evolved on this planet. Studying the history of life through fossils tells us how animals evolve and what processes cause their extinction, be it climate change or low oxygen.”

Nilpena Ediacara National Park opened to the public in early 2023 and is part of a bid to be recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. UNESCO World Heritage Sites are natural or cultural sites considered to be of outstanding universal value and are protected by an international convention.

Researchers said this effort is due in large part to the work and generosity of Mary Lou Simpson, founder and chairwoman of the Flinders Ranges Ediacara Foundation, and her husband Antony Simpson for whom Quaestio simpsonorum is named.

“As the oldest fossil animals, the Ediacara biota, can tell us a great deal about early developmental processes,” Evans said. “Determining the gene expressions needed to build these forms provides a new method for evaluating the mechanisms responsible for the beginnings of complex life on this planet. Because animals today use the same basic genetic programming to form distinct left and right sides, we can be reasonably confident those same genes were operating to produce these features in Quaestio, an animal that has been extinct for more than half-a-billion years.”

Though the team has been excavating at this location for decades — in fossil beds and rock slabs ranging from the size of a fingernail to a several-hundred-pound slab — Quaestio was only recently discovered at one of the newest excavation sites in the park in a collaborative effort with volunteers at the South Australia Museum. The research team hopes to continue reexamining sites throughout the park’s nearly 150,000 acres.

“We’re still finding new things every time we dig,” Hughes said. “Even though these were some of the first animal ecosystems in the world, they were already very diverse. We see an explosion of life really early on in the history of animal evolution.”

To learn more about Evans’ work and research conducted by the FSU Department of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Science, visit eoas.fsu.edu.