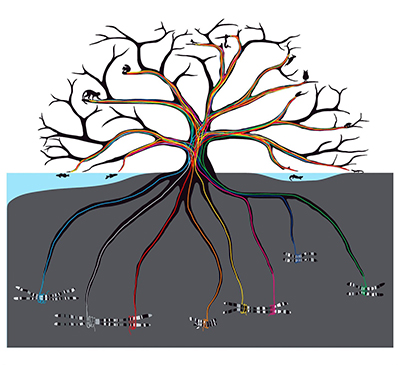

Florida State University’s Center for Anchored Phylogenomics is using a cutting-edge research technique to answer a question that scientists have labored over lucklessly for generations: How do we produce enough genetic data to construct an accurate evolutionary tree quickly and cost effectively?

Thanks to the development of a specialized gene sampling technique by center co-directors and husband-and-wife Alan and Emily Lemmon, FSU researchers have finally begun to chip away at this conundrum — and in doing so, they just might have helped to change the way that we study evolutionary biology forever.

For decades, the process of generating phylogenies (sprawling evolutionary trees) had been tiresome, time consuming and often prohibitively expensive, with hundreds of thousands of dollars being poured into relatively narrow individual studies.

“When we were starting as faculty in 2009, people would collect data for these trees by sequencing one single gene at a time,” said Alan Lemmon, associate professor of scientific computing. “They would sequence a gene, then move on to another species and sequence that gene and repeat that slow process for the dozens and dozens of species that they were investigating.”

This process was onerous, painstaking and costly. Researchers would often need to sequence dozens of genes using this piecemeal method before they could begin generating reliable trees, which meant demanding, resource-intensive projects that would yield limited and sometimes spurious results.

The Lemmons were convinced that there must be a better way.

“We grew up as researchers under these circumstances where we were data starved,” said Emily Lemmon, associate professor of biological science. “To be able to answer the questions that we were asking, we needed lots of data. I had worked in labs where we tried to collect data the hard and slow way, and I knew it wasn’t enough. When we started at FSU, we reasoned that we could either keep doing what everybody else was doing, and it would be guaranteed to work in the same familiar ways, or we could take a risk and try to change the field.”

That risk paid off in spades.

After testing five methods they believed might have the potential to shake phylogenetics from its data-poor rut, the Lemmons identified a completely novel method that could generate staggering amounts of data with unprecedented speed and accuracy.

The Lemmons’ new “anchored phylogenomics method” wedded their expertise in lab work and bioinformatics. Instead of relying on costly fully sequenced genomes, it used advanced probes to isolate and target just a few hundred homologous genes in all organisms of interest to the study. Using these key genomic segments, along with the genetic material that immediately flank these sections of DNA, researchers at the center were able to analyze and reliably decode relationships among vast numbers of species at speeds that far outstripped past methods.

The result was a technique that solved the data problem that had bedeviled researchers for years.

“This method is at least 100 times faster than previous techniques,” Alan Lemmon said. “We can now generate an extremely accurate tree in two weeks that not long ago would have taken years.”

The first paper employing the anchored method was published in 2012, and the scientific community promptly recognized that the Lemmons had created something extraordinary.

“Requests to collaborate started rolling in right away,” Emily Lemmon said. “As of today, we’ve had hundreds of collaborators and have generated data for over 25,000 species.”

The sudden surge in demand for their technique convinced the Lemmons to officially charter the center in 2013. That same year, the researchers enhanced their workflow with a highly-sophisticated sample-processing robot. This allowed the center to better optimize its process and establish itself as a global leader in the field of phylogenomics.

“We spent three years beating our heads against the wall trying to work out this new method, but we knew that if we could get it to work, it would be amazing for the field,” Emily Lemmon said.

In 2015, the center collaborated on a project that represented perhaps the most impressive application of the anchored method to date. Along with researchers from Yale University, the Lemmons conducted a study that definitively resolved the bird tree of life — revealing mysteries of avian evolution that had puzzled researchers for centuries.

“Up to that point, many of the deep and important relationships in birds were still ambiguous,” Emily Lemmon said. “We were able to work out those relationships for a fraction of the cost of other large studies that weren’t able to resolve these really deep relationships.”

Sean Holland, a lab technician in the center, said that when working on these big, groundbreaking projects, he feels that he’s pushing scientific boundaries in new and exhilarating ways.

“You get the sense that you’re always on the precipice of something new when you’re developing these novel methods,” Holland said. “I’ve been involved in the development of completely new molecular techniques that have never been used before.”

In the future, the Lemmons plan to use the anchored method to process samples of frail and degraded ancient DNA. They also are in the process of developing a new systematic technique that would further accelerate the pace of their methodology.

It’s the confidence, intellectual freedom and resources afforded to them by Florida State University, said the Lemmons, that motivate them to continue innovating.

“We couldn’t run a center, generate this quantity of data and publish as many papers as we do without the support of the university,” Emily Lemmon said.

Alan Lemmon concurs, and he also lauded the contributions of the dozens of student and post-graduate researchers that the center has employed, trained and mentored since its inception.

Under the Lemmons’ guidance, and with the benefit unique professional experience at a world-class research center, many of these student employees have been accepted to their top choice programs for medical, veterinary or graduate school, illustrating the life-changing effects of the center’s success.

“We wouldn’t be able to do any of this without the support of the university or without the work of our amazing lab technicians,” Alan Lemmon said.