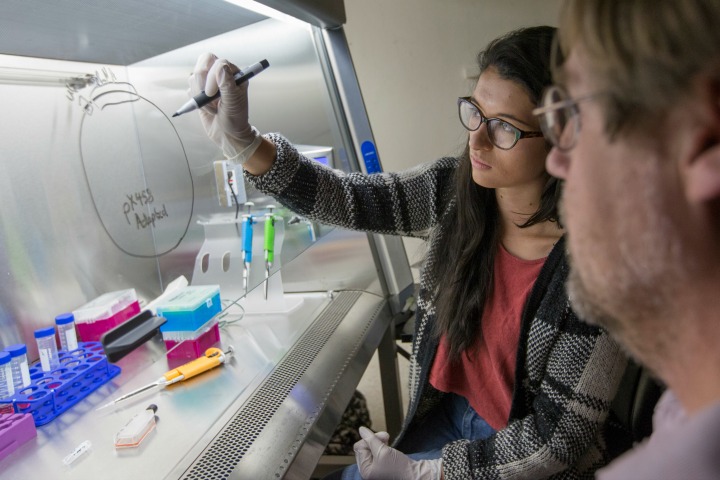

A new Florida State University biology course is providing a group of talented young students with a unique opportunity: hands-on, experimental lab work with the world’s most revolutionary gene editing technology.

The course was designed by Jonathan Dennis, FSU associate professor of biological science, who set out to assemble a curriculum that combined an engaging, individualized classroom experience with access to some of the world’s most advanced gene editing and sequencing technology. The result is an undergraduate class that is unparalleled in its sophistication.

Genome editing, a field of genetic engineering in which particular segments of DNA are targeted for removal or replacement, has experienced a recent surge in popularity and a significant uptick in application. Scientists have long been editing the genomes of model organisms in efforts to conduct research, eradicate diseases and mitigate crop loss, and highly refined editing of complex mammalian genomes promises to be the next frontier.

In Dennis’ class, students work with CRISPR, a cutting-edge gene editing tool that allows researchers to alter and reconstitute genomic material with historically unprecedented levels of precision.

“Maybe three schools in the country have taught CRISPR to undergrads, and roughly a dozen have taught sequencing, but only here at FSU have we put the two together,” Dennis said. “We have undergraduates being exposed to tools that many graduate students will never have access to.”

Short for “Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats,” CRISPR combines a string of pre-programmed guide RNA with an enzyme that functions as a pair of “molecular scissors.” The result is a technique that can target, snip and join strands of DNA with remarkable accuracy.

Few technologies in recent memory have roused the scientific community quite like CRISPR, which has already been applied to combat mosquito-borne illnesses like Zika, to produce yeast-based biofuels and to improve agricultural production.

As this emergent new tool continues to shape the field of gene editing, the work being done by FSU undergraduate biology students puts the university on the vanguard of international CRISPR education and research.

While similar courses throughout the nation have used CRISPR to edit the genes of easily manipulatable organisms like fruit flies, Dennis’ course is singular in its use of human cancer cells.

“We’re doing something that almost no other undergraduates in the nation get to do, and that feels amazing,” said Joe Pelt, a junior in Dennis’ class. “Every morning that I come into lab I feel like I learn something legitimately new that has the potential to change health and science for decades to come.”

The class is structured according to a basic experimental model: isolate a variable, modify it and look for an effect. It just so happens that this particular experiment is being conducted with some of the most sophisticated tools and techniques that contemporary science has to offer.

After the students have selected a gene and edited it out using CRISPR, the cells are then analyzed using next-generation genome sequencing technology in order to detect any phenotypic effects of the gene alteration.

“This is the classic genetic experiment: knock something out, look for an effect and see if you can rescue that effect,” Dennis said. “Our students are using CRISPR and genome sequencing to do an age-old experiment, but in a rocket ship.”

While Dennis’ course does furnish his students with a laboratory experience that is virtually unrivaled among other undergraduate programs, he is quick to point out that his class is also designed to look beyond the microscopes and pipets.

CRISPR is a technology that has already revolutionized the way that we think about the potential of gene editing, and Dennis requires his students to ask probing moral questions about what it means to work with a tool that allows us to engineer genetic material with minute specificity.

“We talk about the ethics of this mechanism all the time in class,” said Sonja Mihailovic, another junior investigating the science and morality of gene editing in Dennis’ course. “We have to understand the power that these tools will give us, and we have to study the ethical considerations — the effects this technology might have.”

Ultimately, Dennis hopes that his students will leave the class not only with an expertise in pioneering new gene editing tools, but also with a more informed perspective on the broad implications of working with a technology that can, as many have phrased it, rewrite the code of life.

“Editing a human genome is almost too easy — if I can teach 19 undergrads to edit any gene in one semester, then the technology might be outpacing the ethical discussion,” Dennis said. “There might one day be people editing human embryos, and we must get out ahead of it in our ethical and moral discourse. My hope is that these students carry on these discussions no matter where they go or what they do.”