As a boy living on a small farm with his grandparents in the Amazon region of Colombia, Juan Carlos Galeano was entranced with the lush, naturalistic and often violent folktales that had been passed down from tribal Amazonians and had evolved through generations of natives and multiethnic newcomers like his relatives.

Over the past decade, Galeano, a poet and professor of Spanish at The Florida State University, returned to the seven countries of the entire Amazon River basin during his summer and winter breaks to immerse himself in the storytelling world of Amazonians and gather and recast many folktales comparable to those he heard in his childhood.

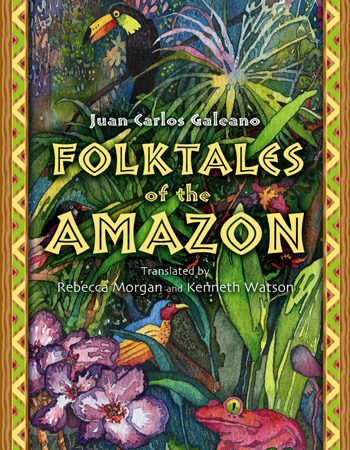

In his new book, “Folktales of the Amazon,” just released by Greenwood Publishing Group, Galeano presents 41 tales gathered and recast from Amazonian fishermen, hunters, lodgers, small plot-farm gardeners and villagers in Venezuela, Guyana, Brazil, Bolivia, Peru, Colombia and Ecuador. This version, translated from Spanish into English by Rebecca Morgan and Kenneth Watson, was previously published in Spanish in Mexico and Peru.

Galeano explained that as the world becomes more technologically driven, the practice of storytelling is decreasing: “Today, we in the so-called first world use the wonders of digital technology to express ourselves, forgetting the importance and function of storytelling. Humankind has been telling stories since thousands of years before the existence of the written word.”

According to Galeano, traditional societies — and Amazonians in this case — use storytelling to recount daily experiences in forests and rivers and to articulate their regard for animals and plants as living, feeling beings.

“Their conception, deeply rooted in Amazonian indigenous cosmologies, is that humans are kin to the non-human world,” he said. “Storytelling is, for them, a way to maintain the memory of costumes and express ethical attitudes toward their land. Unfortunately, the relationship of modernity with these places is one of objectification and demythification as we regard their animals, plants and places as ‘natural resources’ to be used and spent for our comfort.

“What triggered my interest in this project,” said Galeano, “is that with deforestation, the Amazonian population becoming more urban, and the presence of electric lamps and vehicles even in the most remote areas, traditional lore is losing ground. It is important to gather and document those tales before this living library of storytellers dies.”

Organized thematically and reflecting the spiritual and holistic view of the Amazonian indigenous societies, the folktales in Galeano’s book convey messages of kinship bonds and reciprocity, capturing the socialized relationship between animals and people, as well as a variety of shape-shifting supernatural entities. Other stories veer into more shocking or forbidden territory, including acts of cannibalism and the ingestion of psychotropic or visionary plants used by shamans. The book includes stories of pink dolphins, boas and anacondas seducing maidens from riverine settlements, spirit protectors of the forest, and rivers and lakes that are perceived as sentient entities.

In the story “Renacal: A Grove of Magical Trees,” for example, Galeano recounts the experiences of fishermen on the Samiria River and their belief that the ghostly landscape of the Renaco grove hosts spirits who protect animals by punishing greedy fishermen. According to Galeano, stories like this may have served the function of easing the human presence and pressure on areas where animals give birth or lay eggs.

Galeano notes that the shaman plays an important role in Amazonian stories.

“In Amazonia, the presence of the shaman is pervasive and necessary,” he said. “In the forest, where people depend on hunting, fishing and cutting trees for protein and shelter, and where, according to the myths of indigenous peoples, trees, animals and places are considered living beings, interactions between human dwellers and ‘mothers’ or ‘masters’ of trees and animals have the potential for conflict. When this occurs, the mediation of a shaman is needed. Through a shaman’s interpretation of the daily experiences and events, they feed the tradition of oral folklore.”

“Folktales of the Amazon” will be presented at Florida State during the Folklore Festival in the spring of 2009 at the Scholars Commons Room in Strozier Library.

Galeano’s venture into the Amazon is part of a research and creative journey that he says is still unfolding. “Amazonia,” a collection of his poems first published in 2003, was recently translated into a book-length edition in French and has been published in English in several American journals, including The Atlantic Monthly, TriQuarterly and Ploughshares. In 2007, he co-produced and co-directed the film “The Trees Have a Mother: Stories of the Amazon” with faculty and students from the FSU Film School. Galeano also is finishing another collection of poems, “Natural History,” in which he re-mythologizes animals and plants of the Amazon, and he plans to continue the recasting of more tales from areas of the Amazon basin he hasn’t visited yet.