A series of complicated experiments involving one of the least understood elements of the Periodic Table has turned some long-held tenets of the scientific world upside down.

Florida State University researchers found that the theory of quantum mechanics does not adequately explain how the heaviest and rarest elements found at the end of the table function. Instead, another well-known scientific theory — Albert Einstein’s famous Theory of Relativity — helps govern the behavior of the last 21 elements of the Periodic Table.

This new research is published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society.

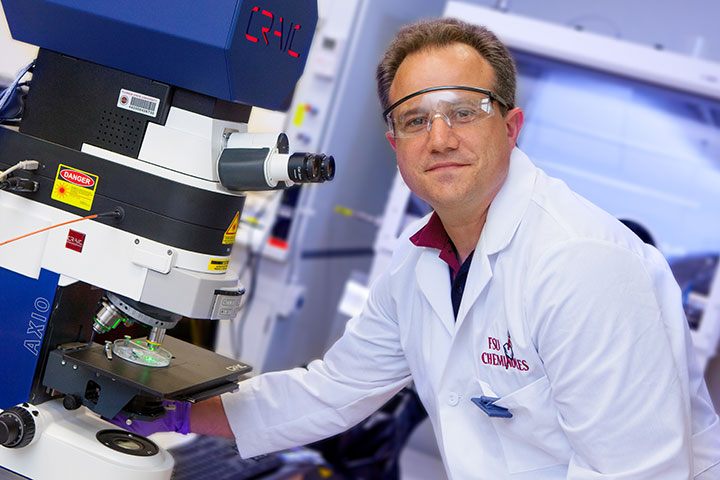

Quantum mechanics are essentially the rules that govern how atoms behave and fully explain the chemical behavior of most of the elements on the table. But, Thomas Albrecht-Schmitt, the Gregory R. Choppin Professor of Chemistry at FSU, found that these rules are somewhat overridden by Einstein’s Theory of Relativity when it comes to the heavier, lesser known elements of the Periodic Table.

“It’s almost like being in an alternate universe because you’re seeing chemistry you simply don’t see in everyday elements,” Albrecht-Schmitt said.

The study, which took more than three years to complete, involved the element berkelium, or Bk on the Periodic Table. Through experiments involving almost two dozen researchers across the FSU campus and the FSU-headquartered National High Magnetic Field Laboratory, Albrecht-Schmitt made compounds out of berkelium that started exhibiting unusual chemistry.

They weren’t following the normal rules of quantum mechanics.

Specifically, electrons were not arranging themselves around the berkelium atoms the way that they organize around lighter elements like oxygen, zinc or silver. Typically, scientists would expect to see electrons line up so that they all face the same direction. This controls how iron acts as a magnet, for instance.

However, these simple rules do not apply when it comes to elements from berkelium and beyond because some of the electrons line up opposite of the way scientists have long predicted.

Albrecht-Schmitt and his team realized that Einstein’s Theory of Relativity actually explained what they saw in the berkelium compounds. Under the Theory of Relativity, the faster anything with mass moves, the heavier it gets. Because the nucleus of these heavy atoms is highly charged, the electrons start to move at significant fractions of the speed of light. This causes them to become heavier than normal, and the rules that typically apply to electron behavior start to break down.

Albrecht-Schmitt said it was “exhilarating” when he and his team began to observe the chemistry.

“When you see this interesting phenomenon, you start asking yourself all these questions like how can you make it stronger or shut it down,” Albrecht-Schmitt said. “A few years ago, no one even thought you could make a berkelium compound.”

Berkelium has been mostly used to help scientists synthesize new elements such as element 117 Tennessine, which was added to the table last year. But little has been done to understand what the element — or several of its neighbors on the tables — alone can do and how it functions.

The Department of Energy gave Albrecht-Schmitt 13 milligrams of berkelium, roughly 1,000 times more than anyone else has used for major research studies. To do these experiments, he and his team had to move exceptionally fast. The element reduces to half the amount in 320 days, at which point it is not stable enough for experiments.

Other institutions contributing to the research are Rice University, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, the University of Buffalo, Institut National des Sciences Appliques in France and the Universidad Andrés Bello in Chile.

The work was funded by the Department of Energy.