Weight training can be a big boost to breast cancer survivors who are trying to regain muscle and bone strength lost due to cancer treatment and physical inactivity, says a Florida State University researcher.

In the academic journal Healthcare, FSU Professor of Exercise Science Lynn Panton details how a weight training regimen can help women who’ve survived breast cancer repair chemotherapy-weakened bodies and help them get back to living their lives.

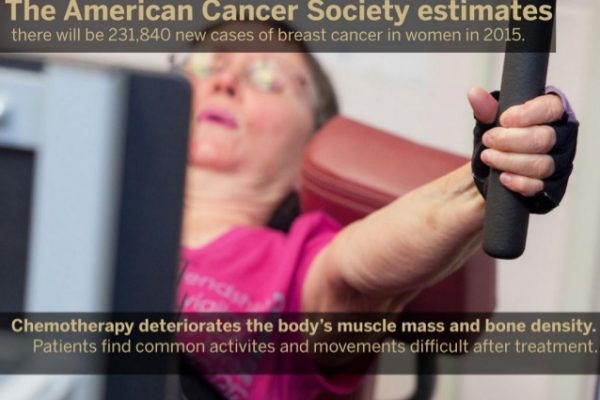

“Cancer treatment causes this accelerated aging,” Panton said. “What we are finding is that many breast cancer survivors are very weak in the upper body.”

Weight or resistance training can reverse many of those problems. In Panton’s study, participants’ physical functionality improved an average of 12 percent after participating in a six-month weight training program at FSU.

For years, many health experts have hailed the benefits of weight training for women, but doctors feared similar recommendations could be harmful for cancer survivors, citing concerns of injury or major swelling in the arms called lymphedema.

Women naturally lose muscle mass and bone strength as they age, but chemotherapy can speed up that process and leave survivors struggling to get through everyday tasks that were once completed without a thought.

Carrying groceries, reaching down to pick something up or walking short distances can become arduous.

Panton’s study showed that a supervised weight training program can make a big difference for these survivors.

Panton and her students worked with 27 breast cancer survivors, ages 51 to 74 years for this study. The women participated in two, one-hour sessions per week where Panton and her students helped them work out using a variety of weight machines. They also walked for five minutes as a warm-up and spent time stretching after the completion of the exercises.

At the end of the study, the participants’ physical functions improved 12 percent. None of the women experienced injuries or lymphedema.

The participants’ functionality was measured by the Continuous-Scale Physical Functional Performance Test developed by Professor Elaine Cress, a University of Georgia researcher. It’s a 10-item test that simulates routine chores such as doing laundry, sweeping, packing and carrying groceries, walking up bus stairs and taking a jacket on and off.

“We had an amazing group of ladies who worked really hard,” Panton said. “They were so motivated. You saw ladies talking about being able to pick up their grandkids and do other things they couldn’t do after their cancer treatments.”

A study just completed by Panton’s team also found that breast cancer survivors had gains in muscle mass and decreases in fat mass after participating in a resistance training program.

The American Cancer Society estimated there would be 1.6 million new cases of cancer in the United States in 2015. Of those, 231,840 are new breast cancer cases in women.

Though treatments are improving the overall outlook for patients, survivors still have a rough road ahead in terms of regaining their prior physical strength and functionality. Exploration of recovery programs is key to their long-term health.

Panton’s team continues to explore this area of research and is looking at other types of programs such as high intensity interval training — commonly called HIIT — to see whether that would be a more effective way for women to regain lost muscle mass and perhaps bone density following chemotherapy.

Panton’s co-authors on the paper are Emily Simonavice of Georgia College and State University and Pei-Yang Liu of The University of Akron. FSU Professors Bahram Arjmandi and Jasminka Ilich and Associate Professor Jeong-Su Kim also contributed.